It took me two visits to Pisa to realize there is plenty more to see than the Leaning Tower and the Piazza dei Miracoli. I recall on my first visit the volunteer at the train station directed us straight to the “only” sight she assumed we dumb Americans wanted to see. On the way, we walked past an adorable little Gothic chapel that was ignored by the crowd of us walking like sheep to see the Leaning Tower of Pisa. I later learned that it was a small church called Santa Maria della Spina, known in English as Saint Mary of the Thorn.

My second visit to Pisa, we took a detour and wandered through some neighborhoods, met university students holding a big protest in Piazza Garibaldi, and got to take a closer look at this elaborately adorned little church. Today, the Santa Maria della Spina is more prominent on Pisa’s tourism website, but I have a feeling many visitors, still just walk past.

Pisa’s Golden Age

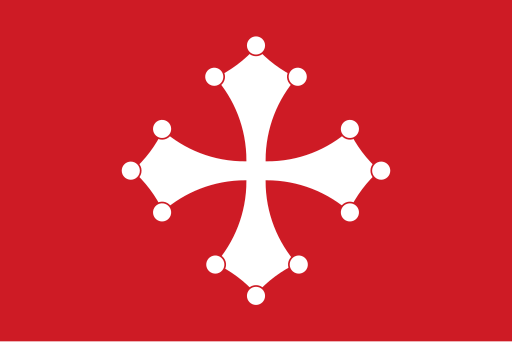

Venice gets all the glory, with her decadent pomp, but there was a time when Venetian galleys rowed for home when the Pisan fleet showed up. Pisa was a force to be reckoned with both militarily and economically in the 11-12th centuries. Their fleet was essential during the First Crusade and their influential Archbishop, Daimbert (Dagobert), basically installed himself as the Patriarch of Jerusalem.

Pisa’s time on top was relatively short, but they made the most of the wealth they accumulated by spending lavishly on their city. The main sights of Pisa, including the Leaning Tower date to this Golden Age, when the Maritime Republic commissioned artists to create a style all their own.

Military losses to maritime rivals eventually stripped Pisa of her military might, but commerce and trade endured for a time. Pisan merchants could be seen in Alexandria, Antioch and Constantinople, bringing both wealth and holy relics back from the Middle East. Eventually the Arno changed course and ended Pisa as a trade center, relegating the city to a historic center of culture and education.

A Prime Example of Pisan Gothic

From: The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Italy

The famous Pisan Romanesque style of the Duomo and Leaning Tower gave way to the Italian variants of Gothic architecture. Pisa has always done things their own way, and so Pisan Gothic stands out in examples like this, and the Duomo’s baptistery, which blend both Romanesque and Gothic.

Compared to other churches in Pisa, especially the imposing Duomo, Santa Maria della Spina is a tiny, compact jewel box adorned with numerous beautiful statues and carvings. Part of its beauty is the amount of adornment on such a small building. The number and scale of the carvings and statues would be impressive on a much larger church.

The original chapel was constructed in the 1230’s jointly by the Senate of Pisa and the noble Gualandi family. It was located right on the bank of the Arno, so that mariners could pray before boarding their vessels. It was, and still is property of the citizens of Pisa and not the local diocese or any religious order.

The original name was Santa Maria in Pontenovo, for the “new bridge” that was built a few decades previously. Many of Pisa’s bridges had small oratories adjacent to them where people could say prayers. The new bridge is long gone from one of the Arno’s many floods. Now the small church sits a short walk from the modern Ponte Solferino.

Starting in 1322, the chapel was enlarged on the orders of the Senate. Work is believed to have been first carried out by Giovanni Pisano. The facade’s Madonna and Child with Angels and the side gallery of Jesus and the Apostles are attributed to him. Work was continued by the workshop of Lupo di Francesco, a former collaborator of Pisano. A second phase of improvements were carried out by Andrea Pisano and his sons Nino and Tommaso.

Credit: Sailko, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The elaborately adorned exterior contrasts to the relatively spartan interior. Modern commenters have often called the interior “plain” but that is only in comparison to the outside. The striped walls and columns of alternating light and dark marble is reminiscent of much larger churches, like the Siena’s Duomo.

Santa Maria della Spina, Pisa

Credit: Gosto, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The Western interior wall once housed the official icon of Pisa: the Madonna del Latte by Andrea Pisano. A copy now occupies the space and the original is in the National Museum of San Matteo. The building is no longer used for religious services, but some impressive sculptures occupy the space once used for the altar. Here Andrea Pisano’s Madonna of the Rose is flanked by statues of Saint Peter and John the Baptist, by his sons Nino and Tommaso Pisano.

A Relic From the Holy Land

From: Tanfani (1871)

The main reason for turning this humble oratory for sailors into a Gothic masterpiece, was to house a relic supposedly from the Crown of Thorns worn by Jesus. How it ended up in Pisa, is naturally, the stuff of legend.

The story begins with a Pisan merchant, who is gifted this Christian relic by a friend. He keeps the relic in Pisa until, after losing his wealth, he flees his creditors in 1266. The relic was now in possession of the Longhi family and once word spread about what they held, several requests were made by local religious organizations.

The pleas of priests and friars were ignored and the family continued to hold onto the Holy Thorn until 1333. Betto di Mone of the Longhi was near death, and donated the relic to the oratory of Santa Maria in Pontenovo. Soon after, the church took on its current name in honor of the sacred thorn. The relic of the thorn was originally placed in silver and gold tabernacle. A new wall mounted tabernacle for the relic was made by Tuscan sculptor, Stagio Stagi in the 16th century.

Controversial Reconstruction of 1871

Credit: Dimitris Kamaras from Athens, Greece, CC BY 2.0

Wikimedia Commons

In 1869 Pisa decided to build up the shoreline along the Arno to protect the town from the dangerous floods that still occur today. The church was in a precarious location right on the bank of the Arno, and the very ground it was built on was subsiding as well, causing damage. Santa Maria della Spina would undergo several restorations starting in the 15th century, but in 1871 the Academy of Fine Arts of Pisa took a different approach.

The work was led by architect Vincenzo Micheli and saw the entire church dismantled, raised one meter higher, and reassembled along the modern road. However the project did not simply raise the structure, controversial decisions permanently altered the church. Many of the original statues were replaced with copies. Perhaps the most controversial decision of all was that the church’s sacristy, built overhanging the river, was never rebuilt.

The Ire of John Ruskin

As it was in 1845 by John Ruskin

John Ruskin, the English writer, philosipher and art historian, fell in love with the little church, calling it ‘my pet La Spina‘ in his writings on Pisa. He has most likely writtten more about the Santa Maria della Spina than anyone else in the English language. In letters he sent during his 1872 visit, he recalls drawing the image seen above. However it was also on this visit that he watched in horror as the “reconstruction” bordered on vandalism.

In the year 1840 I first drew it, then as perfect as when it was built. Six hundred and ten years had only given the marble of it a tempered glow, or touched its sculpture here and there with softer shade.

-Letter 20 (August 1872)

…not a fortnight since (on 3rd May), the cross of marble in the arch-spandril next the east end of the Chapel of the Thorn at Pisa was dashed to pieces before my eyes, as I was drawing it for my class in heraldry at Oxford, by a stone mason, that his master might be paid for making a new one..

-Letter 18 (June 1872)

Santa Maria della Spina is certainly beautiful, but not a pristine example of Pisan Gothic. As you can see, it has been severely altered, mostly for the worse, by the decisions of this so-called restoration.

Current Status of Santa Maria della Spina

Santa Maria della Spina, Pisa

Credit: Gosto Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Santa Maria della Spina is now a historic monument and no longer an active place of worship. The relic of the holy thorn was translated to the church of Santa Chiara. The original sculptures that were taken down during the controversial reconstruction are now in the National Museum of San Matteo. More recent restorations have made the former church sparkle and is both a tourist attraction and art exhibition gallery.

Sources/more information

Commune di Pisa: Santa Maria della Spina

Day & Haghe, et al.. The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Italy: From the Time of Constantine to the Fifteenth Century, Vol II. London: H. Bohn, 1844.

Ruskin, John. The Works of John Ruskin, Vol 27 [Library ed.]. Edited by E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. London: G. Allen, 1907

Tanfani, Leopoldo. Della Chiesa di S. Maria del Pontenovo Detta Della Spina e di Alcuni Uffici della Repubblica Pisana. Pisa: Tip. Nistri, 1871.

Turismo Pisa: Santa Maria della Spina

Varisco, Alessio, Santa Maria della Spina, Un tesoro trecentesco. Antropologia Arte Sacra, 2007

I guess I wouldn’t mind a “plain” interior if I was set to go to sea. It’s the basics that begin to count at times as those.

I love the striped stone they used in Italian churches back then

Very interesting!

Thank you for reading!

A fascinating read and I must admit to being one of those tourists who simply flocked to the leaning tower of Pisa and then left! Sorry to learn of the renovations that robbed the church of some of its beauty, but I will add this church to my next visit to Italy. Thank you. Ciao!

Thank you for reading. I think Pisa is now realizing there is more to their city than just the Duomo and tower.