Note: This is the second part of my tour of the Ypres battlegrounds. Part one is here.

Thinking back as I write this, I’m realizing just how much of my base knowledge of World War I came from this tour. So many important events happened within a day-trip from Bruges that it is staggering. For instance, on our stops, our guide told us the story of the famous Christmas Truce that happened along the front lines here in 1914. We learned about why it is bad luck to light 3 cigarettes with one match (snipers), how horrible trench foot could be, and the fearless rats that swarmed No Man’s Land.

He did such a great job weaving the small stories into the larger ones. I have been a tour guide myself for the better part of 15 years and I wonder if I was somehow inspired by his flawless delivery. Our journey continued along the Ypres Salient to a unique discovery that sadly is gone.

Underground Dugout in Zonnebeke

Outside of Ieper we drove past a brick factory, and into what looked like a construction site near a clay pit. Apparently, while digging they found a preserved underground bunker buried in the clay and perfectly intact. We were part of a select few that were able to visit an actual “dugout” and it was incredible. It was like the Tommies just left, everything was cleared out but the bunks and other furniture was intact.

I contacted Sharon and Philippe to see if they recalled the bunker and they had some bad news. Unfortunately, the site was not properly preserved and within a year, moisture from exposure and visitors completely destroyed the bunker. They told me the wood was so rotten you could push your fingers through it. This is an example of why archaeologist are not always eager to dig something up. Artifacts and dig sites stay better preserved in the ground. If you don’t have a good preservation plan in place, don’t dig it up.

The good news is that even more of these bunkers have been found since then, and have been archaeologically surveyed before being filled back in for preservation.

Hill 60 Memorial

We headed south to the village of Zillebeke and pulled into a serene wooded area as the sky finally let up. This area, bisected by a train line was what remains of two high spots the two forces fought over both on the ground and under it. One was known to the British as Hill 60, for its height in meters, the other across the tracks was known as the Caterpillar. I learned while researching that these are not natural hills, but actually debris piles from digging the railway in the 1850’s. Natural or not, these highly coveted “humps” south of the town of Ypres were destroyed as they exchanged hands in some of the most gruesome and senseless fighting of the War.

Source: Australian War Memorial

Our guide made sure we understood the gravity of this sacred place. This entire park is considered a war grave for the thousands of Allied and German soldiers who were never found. Their remains, along with an unknown amount of unexploded munitions are buried in what is left of Hill 60. Along the now wooded path you see remnants of concrete pillboxes and bunkers peeking through the undergrowth. Rusted lengths of rebar sprout from the ground, like the exposed roots of metal trees and the uneven topography was landscaped by mines and artillery.

©Jan Darthet

A section of boardwalk is marked with the location of the British and German lines and you can see just how close they were at this spot. They were so close they could talk to each other at one point. The Hill was won and then lost by the British during the Battle of Hill 60 in 1915. German heavy bombardment and chlorine gas, along with senseless British attacks saw the casualty rate climb to staggering numbers. The British had over 59,000 casualties in a little over a month during May 1915. It’s hard to even comprehend it. I remember comparing the population of my hometown and imagining twice that number being killed or wounded…in a month.

That would have been bad enough, but the horrors were not over yet. Hill 60 and the Caterpillar were already being tunneled and mined by both sides up to this point. In 1917 the tunneling and mining efforts by the British would intensify to prepare for the Battle of Messines.

Credit: Historical Vagabond

Messines Mines

“Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”

Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army

The current topography and height for Hill 60 is the result of an enormous underground explosion. The British dug tunnels up to 90 feet deep. The goal was to set up mines underneath the German lines along the ridge near the Belgian town of Messines (Mesen) and blow them up from below. There were originally 26 mines filled with explosives, the largest of these at over 40 tons.

At 3:10 AM on June 7, 1917, 20 of the British mines were detonated in a rolling succession. This event is listed among the largest, loudest, and deadliest non-nuclear explosions in human history. It is impossible to determine actual numbers but it has been estimated that 10,000 Germans soldiers were killed in the few minutes it took for most (but not all) of the mines to go off.

Today the hill is not much higher than the surrounding countryside and obscured by nature’s attempt to scab over this wound. It was hard to figure out the lay of the land and where the crater was. I got a better picture of the explosion across the tracks at the Caterpillar, where a peaceful little pond has filled in this man-made crater.

The War in the Tunnels

In a war full of terrifying scenarios, few match the ordeal of the tunnel and mine teams. Their underground battles are the stuff of nightmares, with intense close quarters combat as both sides attempted to blow up the enemy lines from below. French and German forces both tunneled through Hill 60, but the British Commonwealth mining units took it to another level, enlisting actual coal, lead and gold miners from Australia. The 1st Australian Tunneling Company suffered horrible casualties creating a labyrinth of galleries under the ridge before exploding the large mine under Hill 60. A memorial to their sacrifice is located at the entrance, still riddled with bullet holes from when this same ground was fought over in World War II.

Ticking Time Bomb?

Credit: Historical Vagabond

As we made friends with some local pigs next to the park, our guide explained that not all of the underground mines went off as planned. There were two mines that did not go off and their locations forgotten. In the 1950’s one of the mines exploded due to a lightening strike. Philippe had fun playing up the fact that one of these huge caches of explosives still sits somewhere under the local farmland.

At that time, the location of this final mine was truly unknown. The British Army lost the information and so that missing mine could have been anywhere along the Messines ridge. Although the exact location is still unknown, it is assumed that the final mine is located close to the 1950’s explosion site, closer to the French border.

Unexploded Ordnance – The Iron Harvest

When I used to think of countries littered with unexploded munitions, it was usually places like Vietnam or Laos that came to mind. Our 1996 edition guidebook even gave us warnings to stay on paved surfaces in recently war-torn Sarajevo. The thought that modern Belgium was still dealing with arms from the First World War was a shock. Not from the much larger Second World War necessarily, even though this same ground was fought over yet again. The Great War’s carnage was concentrated over a much smaller area and here in Flanders, the all-consuming mud buried it out of sight, but not out of mind.

Credit: Historical Vagabond

We got a first-hand look at the so-called “iron harvest” at a nearby farm with a freshly plowed potato field. On the corner of the plot lay a wooden pallet with an assortment of rusty, but still live and dangerous ordnance. It is truly mind boggling that over a century after the Great War, Belgian farmers still have to risk digging up grenades, artillery shells and even poison gas. Philippe easily identified the nation that made each shell, one of these was a German mustard gas shell.

He told us how it is exciting for locals when a farmer plows a new field because you never know what you could find. It could be anything from a German soldiers spiked helmet to a mustard gas shell. The guide told us a story from his youth of a farmer who hit “something” with his tractor’s plow. When he investigated, he discovered it was a poison gas canister. The army removal team arrived and found that it was in fact an entire stockpile of chlorine gas weapons.

Even though Belgium did not produce any chemical weapons, and very little of the conventional arms, they are responsible for the destruction of these dangerous remnants. Germany, Britain and France made millions of these chemical weapons but at the time of our tour in the 90’s, had not assisted in the remediation of the countryside they left contaminated. Meanwhile, this tiny country needs every bit of its farmland and cannot afford to section off fertile soil just because you may harvest bombs along with your potatoes.

Hooge Crater War Museum

Credit: Historical Vagabond

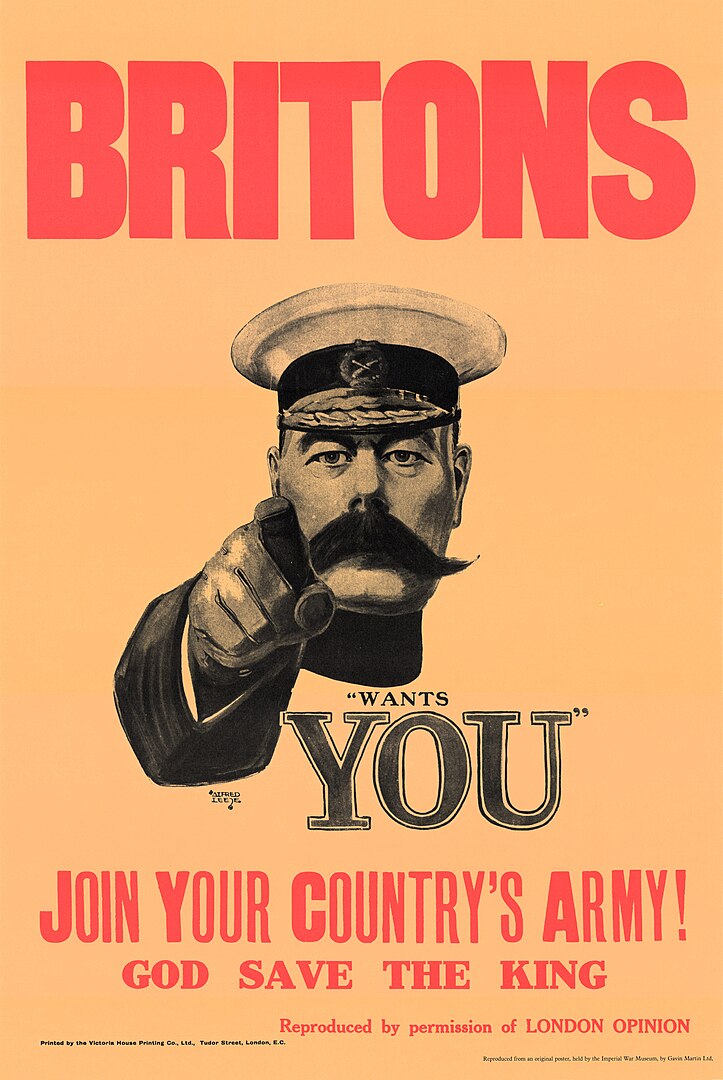

It was about lunchtime when we stopped at a small former chapel turned into a war museum. The Hooge Crater museum was just getting started on our visit, but some of the displays looked familiar when I saw recent pictures. I recall enjoying all the artillery and weapon displays, the different uniforms, but especially the war propaganda posters.

I didn’t realize at the time that our guide had prepared some delicious sandwiches for us. They appreciate good sandwiches in this part of the world – I’ve never had a bad one in the Low Countries. We ate outside the museum at their small picnic area that they have since converted into a cafe.

The group also got to know each other a little bit and share some of their stories about The Great War. Apparently, the three of us didn’t know of any relatives that fought in the war. I assumed as much since my family were recent immigrants to the US.

Bayernwald Restored Trenches

Credit: Historical Vagabond

To the south of Ieper we visited the Croonaert Wood close to the village of Wijtschate. This area was known to the Germans as Bayernwald, for the Bavarian troops originally positioned there. The restored German trenches date from 1916 and are famous for being the area where a young Adolf Hitler was wounded in battle. It’s one of those nexus of history places, where just a slight change of events would have entirely altered the last century.

According to Sharon and Philippe, this is one of only two accurately restored portions of trench in the area. This portion of restored battlefield was not on the front lines, and shows how complex and deep the German trench systems were. Which explains why the British thought it was a good idea to blow them up from underneath. We saw two of the deep mine shaft openings, used to tunnel under the British mining operations during the Battle of Messines. These were, and apparently still are, filled with water, which helps in preserving them. Everywhere we looked were piles of artillery shell casings and rusted metal.

Essex Farm Dressing Station – In Flanders Fields

If I recall, this was our final stop before returning to Bruges, and had the dramatic effect intended for such an important stop. Just outside of Ieper, on the other side of the canal was the Essex Farm Dressing Station and Cemetery. In 1915 this area became an advance medical station with concrete dugouts and makeshift graves.

©Jan Darthet

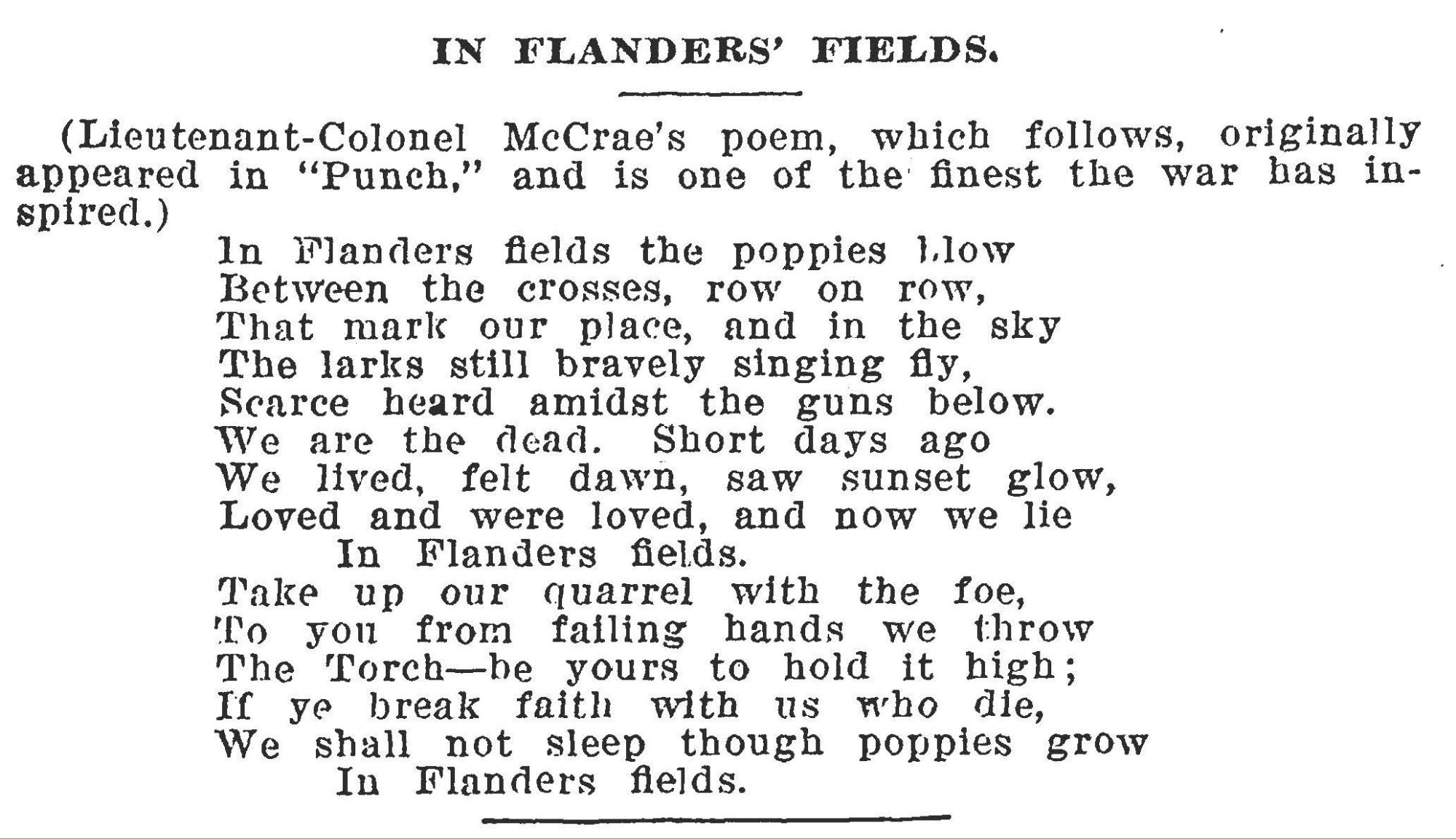

Canadian Major John McCrae was a doctor by profession and tended to the wounded and dying here when stationed with his artillery company. It was here in one of these bunkers, after the horrible death of his friend by an artillery shell, that he wrote THE poem of war: In Flanders Fields. In that makeshift cemetery lined with wooden crosses, McCrae witnessed the red poppies growing among them: Life endured amid so much death.

This area had been recently restored a few years previously, and one bunker had the poem set in a large display. Before this visit, the famous poem was just a poem from High School history class. It was impossible not to be moved standing in that dark, damp concrete dugout, imagining an endless stream of dead and dying men. Their graves, often obliterated by the next artillery barrage. I’m pretty sure the whole group were shedding a few tears by then.

Final Thoughts

Credit: Quasimodo Tours

At the end of the tour, I felt humbled and embarrassed about my ignorance of what happened here in Flanders. The smug 19 year old smart-ass version of me learned a lot that day and changed how I approach the study of war. I stopped thinking about war like a kid and began putting myself – with all my strengths and weaknesses – in the position of one of these soldiers.

My mood changed during the tour, actually all three of us, and the whole busload got a lot quieter and somber as we went along. This was a really fun tour, but not that kind of “fun”. Sure there were plenty of times were jokes where thrown in, but for most of us on the bus, this was all new information and we were just trying to soak it in.

I recall just saying “wow” under my breath and shaking my head in disbelief as I tried to wrap my head around it all. The staggering numbers of unidentified dead, the shattered lives of the survivors, the weapons of mass destruction and the other horrors that took place in a beautiful, but otherwise unremarkable piece of the Low Countries. Young men, cut down in the “flower of their youth” all for a strip of muddy clay. In the end, none of it really mattered. The consequences of the War to End All Wars only lead to the even bigger and more horrific sequel in 1939.

That sobering tour in the fog and rain of Flanders really did change me. I may not have noticed it at the time, but since then, I have grown into the knowledge of tour. It was almost like the experience stayed with me until my brain was mature enough to digest it fully.

This was the kind of experience that has paid dividends years afterwards. It definitely helped in my studies in school, actually walking through trenches and seeing how the Great War’s scars are still in the landscape. Still a part of everyday life for the locals, now over a century removed. Inherited by each new generation and cemented by the nightly ceremony of The Last Post.

If you ever find yourself in Belgium or Northern France I highly recommend that you include a visit to the memorials, museums and cemeteries of the Great War. Let’s not forget the memories of these poor souls…they are certainly not forgotten in “little Belgium”.

A final Thank You to Quasimodo Tours for helping me jumpstart my memory, along with providing many of the images. I highly recommend taking a tour with them, check out their link below.

Sources/More Information:

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Lytton, Neville. The Press and the General Staff. United Kingdom, W. Collins, 1921.

An amazing post.

Thank you.

I appreciate that, thank you for reading.