There was a time in the 19th century when my home port of Gloucester, Massachusetts held a virtual monopoly on trade with the Dutch colony of Surinam, today’s Suriname. It is a foggy part of our local maritime history, that peeks out from the past in the form of Gloucester’s surviving merchant homes, and their fancy portraits and Delftware on display at the Cape Ann Museum. The story told here has always been one-sided and never really covered the Surinamese side, keeping the South American nation and its people, a bit mysterious.

Even today, it is hard to find much about the “Surinam Trade” from the Surinamese side, especially in English. For all the well-written articles declaring the close relations between Gloucester and Paramaribo, it didn’t last long. I wanted to know what was left of this legacy within Suriname itself, partly out of curiosity, but also as a potential lecture at Maritime Gloucester. I began to look for sources within the former Dutch Colony and that is when I learned the surprising fate of these former slave plantations.

The plantation system is gone but in modern Suriname, the former plantation properties still exist. Many have been turned into beautiful resorts, heritage museums and nature parks. There are several former plantations still used for agriculture while others are left abandoned to the jungle. Out of hundreds of former Dutch plantations (plantage in Dutch) there is one coffee producer still in operation: The Katwijk Plantation of Suriname’s Commewijne District. But first, some background on the Dutch Plantations in Suriname and the role New England merchants played.

Suriname Under Dutch Colonial Rule

John Gabriel Stedman (1796)

Engraving by William Blake

At the end of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch Republic obtained Suriname (also known as Dutch Guiana) from England, in exchange for New Netherland, including New Amsterdam (today’s New York City). The flat, fertile land on the eastern side of the Suriname River was like a tropical Holland and soon the Dutch were cutting canals through the rain forest and flood plains. They named the area Commewijne in the late 1660’s. This was the heart of the Dutch plantation system, where African slaves worked to produce cash crops like cotton, sugar and coffee.

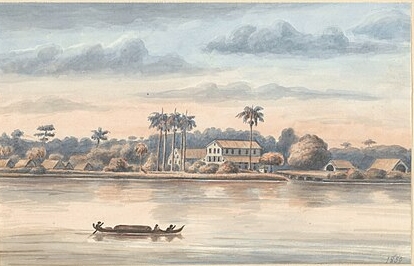

The Dutch protected their prized colony from pirates and rivals with Fort Nieuw Amsterdam, built at the confluence of the Suriname and Commewijne Rivers. By 1800, there were an estimated 600 plantations in Suriname, many, like Katwijk, were named after areas or towns in the Netherlands.

Louise van Panhuys (1763-1844)

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Foreigners to Suriname in the 18th century were often shocked at the level of cruelty by the Dutch plantation owners and their managers. In the days of the active slave trade, plantation owners had access to plenty of labor, so long as they had the funds. They worked slaves to death and simply bought new slaves to replace them. This led to slave revolts, with escaped slaves fleeing into the jungle. They often cohabited with the indigenous population and created a unique offshoot of Caribbean culture known as the Maroons.

The soldier, adventurer and writer John Gabriel Stedman documented his time fighting the Maroons in Suriname in his Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam. Stedman was no saint, and certainly no abolitionist, but had much to say about how badly the slaves were treated in Suriname. Inhumane punishments, rapes, murders, even infanticides were just part of the fabric of the Suriname plantations of the 1770’s.

Suriname Trade with New England

John Greenwood (1755)

St. Louis Art Museum, Public Domain

New England trade with the Caribbean goes back to the earliest days of the colonies. Numerous small ports had merchant fleets that traded, both legally and illegally, with the various European colonial powers. In time this trade would consolidate in just a few ports, before Boston absorbed virtually all foreign trade. New England captains, crews, merchants and their families were a frequent sight in the capital city Paramaribo.

These wealthy merchants made the most of their time in sunny Suriname, getting blind drunk and gambling away their profits were just the tip of the iceberg. They had palatial homes, house slaves, some even had second families. Quite a few New Englanders died and were buried in Suriname. The intense tropical heat along with malaria were an ever-present threat, but worse was the arrival of yellow fever. If a sailor got infected it could spread, decimating a crew. Their distinctive gravestones are usually seen in Puritan burying grounds and look out of place in Paramaribo’s cemeteries.

Salt Fish for Molasses and Coffee

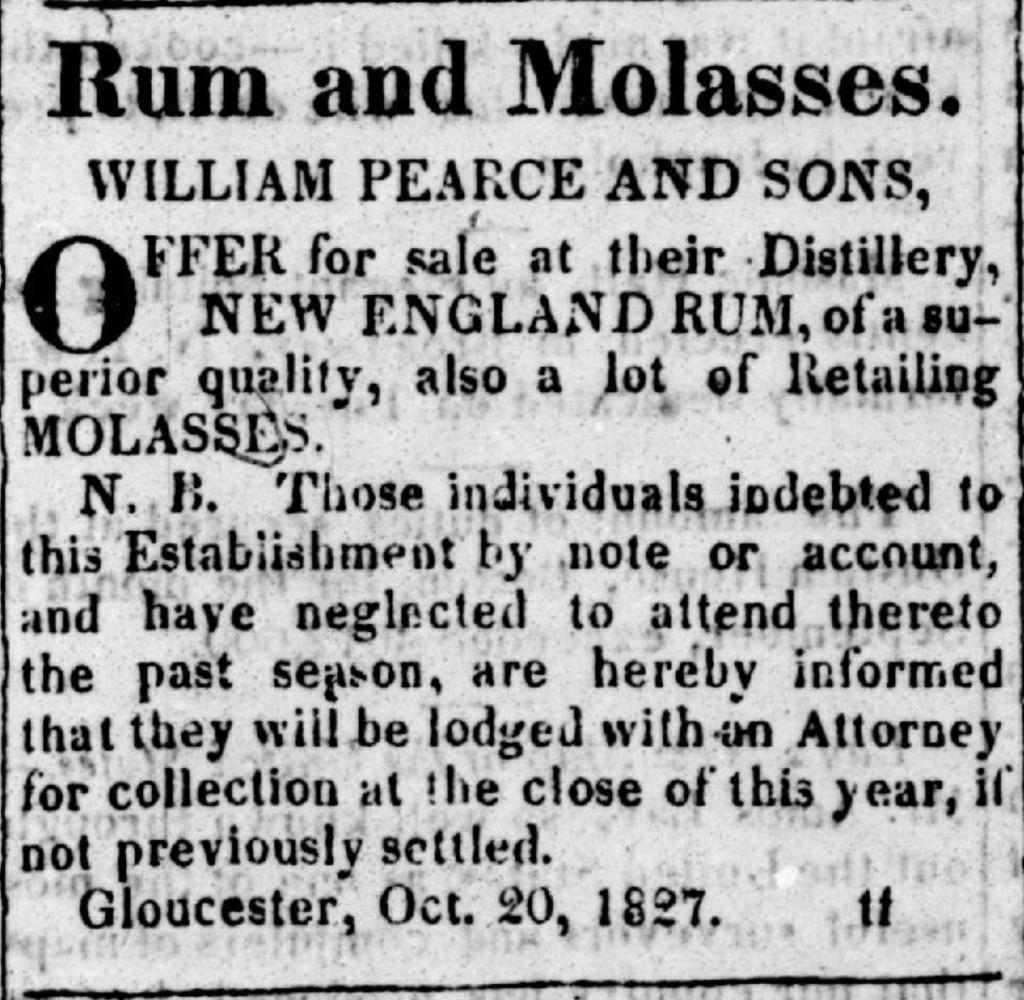

to make a celebrated New England rum on the Gloucester waterfront.

Gloucester Telegraph: November 10, 1827

The Surinamese slaves were mostly occupied growing cash crops, so plantation owners had to find ways to keep them fed. This is where the port of Gloucester made its mark in Suriname. Starting in 1810, the firm of William Pearce and Sons sent the first local vessel to the Dutch colony. The merchants of Gloucester were “vertically integrated” owning their own wharves, vessels and were often ship captains. This allowed for a firm hold on this leg of the infamous Triangle Trade of goods, gold and slaves, for about fifty years.

The merchant families of Gloucester were primarily involved in shipping salt fish and produce to feed the plantation slaves. This was not the famous salt cod, but salted hake, a related fish of lesser value that was caught by vessels in the shore fisheries of the Gulf of Maine. One Gloucester observer, visiting in 1859, claimed the slaves in Suriname preferred the salted hake to salted cod. The salt cod sent as slave food was usually off-cuts labeled as “junk” while better quality hake was readily available. True or not, it gave the subsistence-level fishermen, who worked the coast “haking” in small boats, a larger market for their small catches.

In return, New England merchant captains brought back coffee, sugar, molasses, tropical fruits and Dutch finished goods. This was a boon for merchants on both sides since the Napoleonic Wars cut off Suriname from European markets and the War of 1812 did the same to the young United States. The early years of this trade must have been good, since it continued and expanded, in peacetime.

Rijksmuseum, Public Domain

There was no shortage of men willing to “go Surinaming” (yes, that was what they called it) since the voyage took place during the coldest months of the year. Gloucester had a large mackerel fishing fleet at that time, which tied up until the flashy fish came back in the spring. The mackerel fishermen could crew on one of the Suriname vessels and spend a few months not only enjoying the tropics, but also making money. They would return right on time to outfit the mackerel fleet in the spring and fish right until the late fall.

This trade was not always profitable, prone to booms and busts. Many top merchants would see their fortunes dwindle by the end. One exception was a brief boom right before Boston took over in the 1860’s. In 1857, 10 barques and 10 brigs arrived in Gloucester with cargoes valued at $400,000 ($14.6 million today). In their turn, Gloucester sent 16 vessels to Suriname loaded with fish, beef, pork, soap, candles and cooking oil valued at $300,000.

When Gloucester’s top merchant George Rogers moved to Boston in 1860, the Gloucester Suriname firms either relocated, or closed. By that time Gloucester was firmly established as the salt cod, and fresh halibut capital of the Western Hemisphere. In the aftermath of the American Civil War, and the growing tragedies to its fishing fleet, Gloucester shifted focus. The Boston trade lingered on for little more than a decade, fading out sometime in the 1870’s.

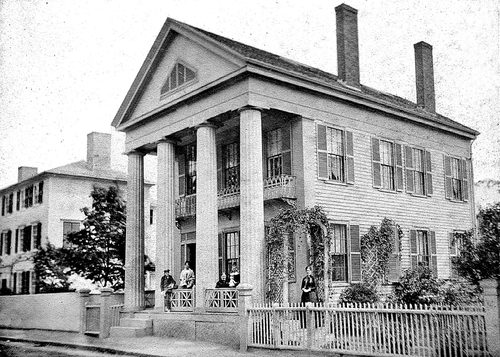

Demolished in 1965

Gloucester didn’t immediately forget, but as time went on, it became a secondary, almost nostalgic story as the fishing fleet grew in both fame and economic importance. Occasionally, a surviving member of the of “Old Surinam Trade” would have recollections published in the Cape Ann Advertiser or the Gloucester Daily times. The surnames of the old sea captains still reside in Gloucester and some, but sadly not all of their stately Federal and Greek Revival mansions can still be found downtown.

End of Slavery in Suriname

It seems that most plantations were not very profitable in the final decades of the slavery era. The slave trade was banned in 1808 and with it began a labor shortage that would eventually be the downfall of the plantations. Foreign observers of the 1850’s mention the plantations of that time ran on daily quotas, and once the slaves had produced it, were then able to hunt, farm or fish for themselves. This was a slight improvement from the early days of Dutch plantations, but it was still slavery and it was still cruel.

Continually during my visit to Surinam, slave owners were trying to impress upon me the perfect state of felicity of their slaves, and the absence of all corporeal punishment. This continual cry of stinking fish awoke my suspicions, and on inquiring of an overseer, a German, one day, he confessed the whipping was severe and frequent.

– Edward Sullivan esq.

Plantation owners anticipated the end of slavery for nearly a decade and began to adapt the system to keep operating. Some former slaves continued to work on the plantations after Dutch emancipation in 1863 in a form of indentured servitude for ten years. However, even before emancipation, foreign labor was brought in to keep the system going.

Arrival of Indentured Foreign Labor

Credit: Wereldmuseum, Amsterdam

This was the start of the “coolie” era of plantation labor with Chinese laborers first brought in starting in the 1850’s. Approximately 2500 Chinese workers came to Suriname over a ten-year period to work the plantations. Many stayed in Suriname once their contracts were completed, although Chinese-Surinamese make up a small ethnic minority today.

A treaty between the Netherlands and Great Britain began the introduction of Indians in the 1870’s Today Indo-Surinamese, also known as Hindustani are the largest of the ethic groups. . The Dutch East Indies was the source for Indonesian contract labor starting in the 1890’s. Indonesian laborers, mainly from the island of Java continued until the start of World War II in 1939. Today many Javanese-Surinamese still live in the Commewijne District, but a large portion moved to the Netherlands starting in the 1970’s.

Demographic statistics alone cannot explain the racial, ethnic and cultural mix of the Surinamese people. From this oppressive history of slavery and indentured servitude has emerged one of the most culturally and ethnically diverse populations you will find anywhere.

The Story of Katwijk Plantation – Plantage Katwijk

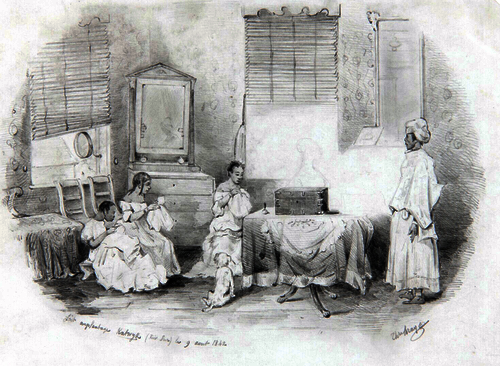

The Creole housekeeper was known as a Sisi

By Théodore Bray (1842)

Wereldmuseum, Amsterdam

The story of Katwijk mirrors the experience of many of the Suriname plantations. Katwijk is still an active plantation, but it was not always in high level operation, or even profitable, but shows the long and sometimes turbulent history of these properties.

Located on the south bank of the Commewijne River, Katwijk was issued by Governor Mauricius in 1746 to thirteen year old Alida Maria Wossink from Paramaribo. The teenage girl was now the owner of 500 acres and 30 slaves and would later acquire several other plantations as well.

In 1748, she married Christiaan De Nijs from Duivenvoorde, owner of the Imotapi and Nieuw Ribanika plantations. Shortly after the marriage, De Nijs expanded the Katwijk operations thanks to a large loan in 1755. A 1759 inventory shows that Katwijk was a large coffee plantation of that time with 159 slaves, and an assessed value of over 150,000 Dutch Florins. John Gabriel Stedman was familiar with Alida Wossink and her third husband, describing them as some of the most brutal slave owners in Suriname.

Change in Ownership – Change in Crops

Wereldmuseum, Amsterdam

The property began to have financial difficulties due to the 1755 loan and Katwijk was foreclosed. New ownership arrived and in 1830 Katwijk was a reasonably profitable coffee plantation with 146 slaves producing 17,000 kg of coffee. However, coffee cultivation exhausted the soil and yields began to decline.

In 1850 Katwijk gradually switched to banana cultivation for the local market. That first year Katwijk produced 2300 kg of coffee and 5000 bunches of bananas. A decade later 35,500 bunches of bananas were produced and no coffee, but the plantation owners would eventually reintroduce it.

Levi Bixby: Yankee Plantation Owner

Levi Bixby was an American merchant from New Hampshire that operated a successful mercantile business from Paramaribo starting in the 1830s. The Bixby family split their time between the homestead in New Hampshire and their beautiful manor home in Paramaribo. The large manor along Paramaribo’s Waterkant was maintained by 13 house slaves in 1846. The Bixby trading company operated out of an impressive building that is now the Suriname Ministry of Natural Resources.

Bixby became the United States Consul to Suriname for about ten years, while his sons began to take over the business. When his tenure was over, Levi Bixby, already a slave owner, became a plantation owner with the purchase of Katwijk Plantation in 1853. However, the sale did not include the 139 slaves that worked Katwijk. Bixby brought in 66 Portuguese workers from Madeira to keep Katwijk operational, an early example of imported labor in Suriname. The next year, Bixby transferred slaves he owned from another plantation, over to Katwijk.

Levi Bixby died in 1856 and was buried in the Nieuw Oranjetuin cemetery in Paramaribo. His heirs operated Katwijk Plantation until 1862 when it and the slaves were sold at auction to Dr. J.J. Juda.

Emancipation at Katwijk

Dr. Julius Jacob Juda was probably not a typical plantation owner. He was a Doctor of medicine, surgery and obstetrics who was unmarried, and lived with his two sisters in Paramaribo. His brother Henri helped him manage the property, which was now without a labor force. Dr. Juda was financially compensated for Katwijk’s 128 emancipated slaves and hired British-Indian and Javanese contractors to continue the plantation business.

Production Under Immigrant Labor

Wereldmuseum, Amsterdam

Juda owned Katwijk until 1895 and underwent several ownership changes until the 1920’s. During that time hundreds of Indian and Javanese laborers were brought in. In 1906 Katwijk had 196 workers, 153 of which, were immigrants. Although Katwijk had twice the labor force as the surrounding plantations, its production was very poor.

In 1906 the plantation produced 2155 kg of cocoa, 327 kg of coffee, 465 bunches of bananas, and 750 kg of grain. It seems like a lot until realizing the other plantations produced up to 5 times more. In 1907 the workforce was increased to 267, but production only increased slightly.

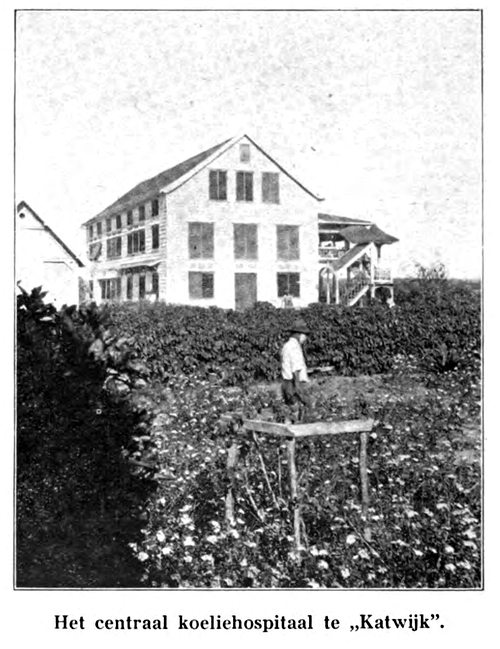

In 1926 a central hospital was established at Katwijk to service the needs of the plantations along the Commewijne River. This was an improvement to the inadequate facilities usually found at each plantation.

WWII: Katwijk Internment Camp

In 1942, Katwijk Plantation and Hospital served as an internment camp for prostitutes and gang members. With the arrival of American soldiers to protect Suriname’s bauxite mines, prostitution kicked into high gear. This coincided with a visit by Princess Juliana of the Netherlands and the rise in sexually transmitted diseases led to prostitution raids. The most famous of those imprisoned was Maxi Linder, an influential Surinamese prostitute, madam and entrepreneur. Most of the convicts would not be freed until 1944.

After the War, Suriname’s plantations lingered on but labor shortages, and low prices for sugar and coffee meant that they could not compete. Katwijk lingered on, producing small amounts of coffee and citrus fruits right up until Surinamese Independence in the 1970’s.

Katwijk Plantation Today

Many of the old plantations, including Katwijk, are operated as tourist resorts, similar to an Italian “agriturismo” where old farmsteads supplement production with guests. Katwijk is considered to be the last active coffee plantation in continuous operation but also caters to the growing markets of heritage and nature tourism.

Katwijk has been owned by the Nouh-Chaia family since the early 1970’s. The family’s business portfolio also includes the Readytex Gallery and souvenir stores in Paramaribo. Here they sell their locally popular artisanal Katwijk coffee sold under the “KW Koffie” label. Suriname is just starting to have a “coffee culture” and so most of what is grown has historically been exported to The Netherlands. That is starting to change in part due to tourism, but the streets of Paramaribo are not lined with cafes just yet.

Katwijk’s status as the last coffee producer in Suriname is no longer certain, as several former plantation properties are getting back into coffee production under new ownership. What keeps these former plantations from becoming major producers is the same old problem: shortage of labor and a tricky economy.

Final Thoughts

Credit: Plantage Katwijk

My research continues for vestiges of the old New England-Suriname relations and I have learned a lot so far. Learning that the graves and homes of the old merchant captains are still in Paramaribo was certainly an eye-opener. But the fact there is still an active coffee plantation, once owned by a Yankee merchant, was the biggest surprise.

Plantage Katwijk is a good case study on the evolving role of these plantation properties from colonial times to modern Suriname. It has been witness to the worst of slavery, the maroon wars, the first waves of immigrant labor, and the slow road to Surinamese independence. Through centuries, this hard worked tropical soil along the Commewijne River has almost single handedly kept up the coffee growing legacy.

A big thank you to Monique Nouh-Chaia of Plantage Katwijk, Georgetine Nremoredjo, from the National Archives of Suriname and to Bas Spek of the Bakkie Museum for their help with this research.

Sources/More Information

Cape Ann Advertiser, Gloucester Daily Times. Digitized by Sawyer Free Library/Advantage-Preservation

Dikland, Philip, De Koffieplantage Katwijk aan de Commewijnerivier. National Archives of Suriname 2001, supplemented 2008, 2010.

Plantage Katwijk Facebook Page

Museum Bakkie: Former Reynsdorp coffee plantation restored into a museum

Stedman, John Gabriel. Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam: In Guiana … From the Year 1772 to 1777 ; Elucidating the History of That Country And Describing Its Productions, Viz. Quadrupeds, Birds, [etc.] Trees, Shrubs, [etc.] With an Account of the Indians And Negroes of Guinea. 2d ed., cor. London: J. Johnson, 1806.

Sullivan, E. Robert. Rambles and scrambles in North and South America. London: R. Bentley, 1852.

Sypesteyn, Cornelis Ascanius jonkheer van. Beschrijving Van Suriname, Historisch-, Geographischen Statistisch Overzigt, Uit Officiele Bronnen Bijeengebragt Door. ‘s Gravenhage: Gebroeders van Cleef, 1854.

Another fascinating disclosure of a hidden history….thank you!

My pleasure, thank you for reading!

Fun fact: “maroon” is also a verb, meaning to cast oneself away – struck me as vocabulary from “Robinson Crusoe” who was supposed to be farming in Brazil before getting “marooned” in the Caribbean. But the older meaning was probably that noun for slaves who escaped the plantations regime.

Glad, and sad, to learn about this unfamiliar period of entwined New England-Dutch-Latin American history.

Thanks for reading Mitch. I hope to dig deeper in the future.