Overlooking the Arch of Septimius Severus is a small but unique church complex that houses the Carcere Mamertino or Mamertine Prison. This has been a place of Christian veneration since at least the Middle Ages, but its history goes back to the early days of the Roman Kings as a holding cell. If you happened to make Rome’s most wanted list, chances are you ended up in here. This inescapable prison was Rome’s “Death Row” regardless if you were an enemy of the Republic, a defeated king or Christian saint.

The Mamertine Prison did not go by that name when it was an actual prison. By the early Middle Ages, enough Roman history had been corrupted that historic monuments began to take on different names. The Flavian Amphitheater became the Colosseum and the now-buried Roman Forum was known as the Campo Vaccino – the cowfield. The 16th century church that is built above the ancient prison was once known as San Giuseppe a Campo Vaccino. The word Mamertine or Mamertino is probably Medieval in origin, based on an ancient temple to the god of war, Mars.

The Tullianum

“There is a place called the Tullianum, about twelve feet below the surface of the ground. It is enclosed on all sides by walls, and above it is a chamber with a vaulted roof of stone. Neglect, darkness, and stench make it hideous and fearsome to behold.”

– Sallust: War with Catiline (LV)

In early Roman times this was known as the Tullianum and was originally a cistern for the spring that still flows in the floor. It was supposedly commissioned by the fourth King of Rome, Ancus Marcius sometime after 640 BC. Alternatively it may have been constructed by his predecessor, Tullus Hostilius, based on the name.

It is uncertain when the cistern began to be used as a prison, since Ancient Rome did not use long term imprisonment as a punishment. The convicted lower class citizens and slaves could be sentenced to hard labor at the nearby Lautumiae quarry as punishment. The Tullianum was not for long term imprisonment anyway, it was Rome’s holding cell, located near the courts in the Forum.

A few centuries after the cistern was created, an upper level was created, called the Carcer. This was the street level “processing area” above the dungeon below. Once lowered through a small opening in the stone floor, there was no escape for Rome’s most important enemies. Most prisoners would be taken from the Tullianum, put on trial and sentenced to death via several variants of Roman capital punishment.

Capital Punishment in Ancient Rome

©Riccardo Auci/Opera Romana Pellegrinaggi

The Tullianum was not only convenient to the Roman court, but also to the traditional spots of execution. The earliest of these places of execution was the Rupes Tarpeia or the “Rock of Tarpeia”, a cliff on the south side of the Capitoline Hill. Since the days of Rome’s kings, convicted thieves, murderers, traitors and even infants with birth defects, were thrown to a dishonorable and humiliating death.

Closer to the prison were the Scalae Gemoniae the “Stairs of Mourning.” A staircase leading to the Capitoline Hill and that began to be used as a site of execution in the early days of the Empire. The bound and strangled bodies of Rome’s dishonorable enemies were left to rot on the stairs as a grizzly reminder to all. The Carcer/Tullianum and the stairs were intentionally conspicuous, looming over the public in the Forum. This fate could befall any of them. The Emperor Vitellius for example, had his 8-month reign ended here during the Year of the Four Emperors in 69 AD.

©Riccardo Auci/Opera Romana Pellegrinaggi

For the elite enemies of Rome, such as defeated kings and generals, their end often came after the famous Roman triumphal march through the Forum, up to the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline. The Roman-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus describes the execution of Simon ben Gioras in the Forum, at the finale of Emperor’s triumph.

“The procession finished at the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitol, where they came to a halt: it was the custom to wait there till news came that the commander-in-chief of the enemy was dead. This was Simon, son of Gioras, who had been marching in the procession among the prisoners, and now with a noose thrown round him was being dragged to the usual spot in the Forum while his escort knocked him about. That is the spot laid down by the law of Rome for the execution of those condemned to death for their misdeeds. When the news of his end arrived it was received with universal acclamation, and the sacrifices were begun.”

– Flavius Josephus: Jewish War, VII.5.6

The end was not so grand for many other captives of the Tullianum. In the case of the Cataline conspiracy of 63 BC, the prisoners never made it to the court. They were executed without trial in the Tullianum, on the orders of Cicero. Many other prisoners, former kings included, were simply dropped into the hole and left to starve to death. There is a small door in the complex that leads to Rome’s ancient sewer known as the Cloaca Maxima, where the bodies were possibly dumped.

Famous Prisoners of the Mamertime

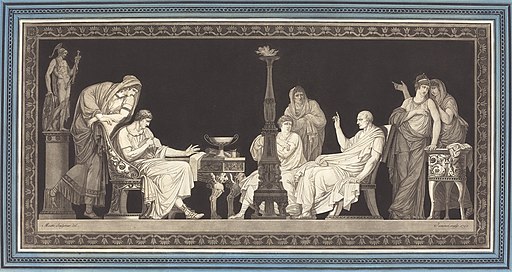

Jean-François Janinet after Jean-Guillaume Moitte.

National Gallery of Art.

Cataline Conspirators (Executed: 63 BC) – Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, Marcus Caeparius, and three other conspirators in the failed Cataline Conspiracy, were arrested and imprisoned. They were strangled within the prison on December 5, 63 BC, on the orders of Cicero. His justification was that the conspirators, as enemies of Rome, had forfeited their rights as Roman citizens.

Jugurtha (Executed: 104 BC) – King of Numidia whose actions and bribes angered Rome leading to the Jugurthine War. He was betrayed, captured and send to Rome in chains to be paraded in the triumphal march of Gaius Marius. He was thrown in the Tullianum, where he was either strangled or starved to death in the prison.

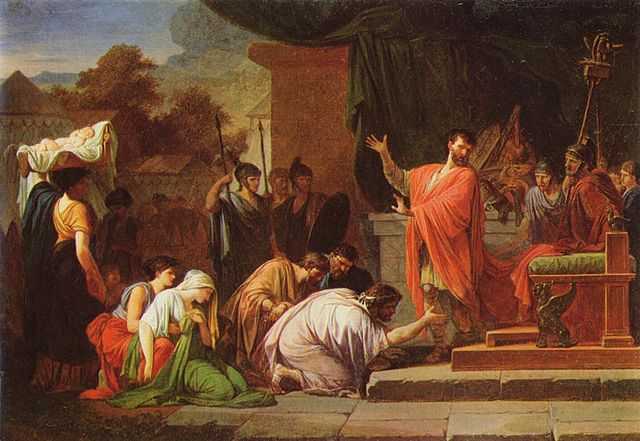

Jean-François Pierre Peyron

Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Perseus of Macedon (Executed: 166 BC) – The last king of Macedonia was defeated at the Battle of Pydna, ending the Third Macedonian War. Perseus was imprisoned in Rome with his half-brother Philippus and son Alexander. He was captured and imprisoned in the Mamertine before the triumph of Aemilius Paullus in 167 BC.

Simon bar Giora (Executed: 70 AD) – A leader of the First Jewish War against Rome, his tumultuous reign led to the destruction of the Second Temple and eventually his capture amongst its ruins. He was held in the Tullianum until paraded in Emperor Vespasian’s triumph, and then executed. The plaque in the Mamertine states he was decapitated, while Josephus seems to allude to strangulation in the Forum. However, he may have been tossed from the Tarpian Rock as a traitor.

Supporters of Gaius Gracchus (died 121 BC) – Many followers of the reformist tribune Gaius Gracchus were executed here by strangulation after his death. Even though many of his reforms were kept, his followers were purged, some without trial.

Lionel Royer

Musée Crozatier

Vercingetorix (Executed: 46 BC) – The famous chieftain of the Arverni tribe who led a major Gallic revolt against Julius Caesar. The Gallic leader is said to have surrendered to Caesar in dramatic fashion after the Battle of Alesia in 52 BC. However Plutarch may have been embellishing the story:

And the leader of the whole war, Vercingetorix, after putting on his most beautiful armor and decorating his horse, rode out through the gate. He made a circuit around Caesar, who remained seated, and then leaped down from his horse, stripped off his suit of armor, and seating himself at Caesar’s feet remained motionless, until he was delivered up to be kept in custody for the triumph.

-Plutarch: Life of Caesar, 27.9-10

Vercingetorix languished in the Tullianum for nearly six years before being executed at the end of Julius Caesar’s first triumph in 46 BC.

Traditions of Saints Peter and Paul

Valentin de Boulogne

Vatican Museums

With the transition from a pagan to a Christian empire, the former prison became identified with the imprisonments of Saints Peter and Paul. There is no evidence that the Apostles were ever imprisoned in the Mamertine, but it was certainly plausible, based on its history. Local legends coalesced, creating a narrative accepted as truth by at least the 4th century AD.

The 6th century Acts of Saints Martinian and Processus tells the story of the conversion and martyrdom of the former Roman prison guards. Their relics are located in St. Peter’s Basilica and their feast day is held July 2.

The two Apostles were in Rome during the time of Emperor Nero’s persecutions of Christians and were arrested. A magistrate named Paulinus held them in the Tullianum, where they languished for 9 months. The Apostles were said to be healing their fellow captives, when their prison guards, Martinian and Processus asked to be baptized. A legend grew that Peter struck the rock in the floor and a spring flowed so he could baptize the guards and over 40 fellow prisoners. Apparently, the prison’s original use as a cistern had been forgotten.

Martinian and Processus freed Peter and Paul, but their freedom was short lived. Both Peter and Paul were executed sometime between 64-68 AD, during the final years of Emperor Nero. Paul, Martinian and Processus were Roman citizens and so were beheaded, with Paul’s head supposedly bouncing three times, creating springs along the way.

Annibale Carracci

The National Gallery London

Peter’s story continues into another famous legend known as Quo Vadis, Latin for “where are you going?”. While fleeing Rome along the Appian Way, Peter was met by the risen Jesus, carrying a crucifix. Peter asked Jesus where he was going (quo vadis?) and Jesus replied “to Rome to be crucified again.” It was then that Peter understood what he must do and headed back to Rome. Peter was crucified at the Circus of Nero, current site of Vatican City. He was crucified upside down, at his request, according to the 2nd century Acts of Peter.

From Roman Prison to Place of Worship

©Riccardo Auci/Opera Romana Pellegrinaggi

According to Medieval legend, the prison was turned into the San Pietro in Carcere (St. Peter in Prison) church in the 4th century, during the pontificate of Pope Sylvester I. It is unknown exactly when the Tullianum ceased to be a prison, but excavations in 2010, led by Dr Patrizia Fortini discovered evidence of Christian worship by at least the 7th century AD.

The name San Pietro in Carcere refers to the Mamertine/Tullianum portion of the complex. The new church incorporated the two levels once known as the Carcer and Tullianum respectively, now better known as the Mamertine. A set of stairs were installed to access the former holding cell below. Along this short stairway a disfigured stone in the wall grew into another legend. The stone is said to have the imprint of Saint Peter’s head, left there from where a Roman guard pushed him into the wall.

Excavations and restorations in the 21st century were finished in 2016, creating a small museum on the upper level of the Mamertine. The altar and ancient column from the lower level were moved to this new space to help better tell the story of this sacred place.

San Giuseppe dei Falegnami

This historic and sacred site was a popular stop on the pilgrim itinerary, but never practical for large scale worship. In 1540 the Congregation of the Carpenters rented the church of San Pietro in Carcere for meetings and religious functions. However, this church was too small for their needs and starting in 1597 a new church was begun over the prison. San Giuseppe a Campo Vaccino, today known as San Giuseppe dei Falegnami was finished in 1663 and consecrated to Saint Joseph, patron saint of carpenters.

In 1853, the Chapel of the Crucifix was built between the church’s floor and the prison’s ceiling and contains the Santissimo Crocifisso di Campo Vaccino. This is a late Medieval crucifix with supposedly miraculous powers. In the 1930s, the facade of the church was altered to allow direct access to the Mamertine Prison from the street.

Final Thoughts

There are few places where the past and present coexist like in Rome, it’s what keeps the Eternal City…eternal. This effect is really felt within the confined space of the Mamertine. To borrow from physics for a moment, the lower level of the Mamertine Prison is like a historical singularity. This former ancient cistern and prison, is a place where the stones are literally dripping with history. When you visit this small dark and still damp ancient prison, events of the past envelop you.

A special thank you to Francesco Lurago of the Opera Romana Pellegrinaggi for providing information and images.

Sources/More Information

Archconfraternity of San Giuseppe dei Falegnami

Encyclopedia Romana: Tullianum

Omnia Vatican Rome: Mamertine Prison

Plutarch, George Long, and Aubrey Stewart. Plutarch’s Lives, Translated From the Greek. London: G. Bell and sons, ltd., 1925