It is well known that Italy’s rich volcanic soil is great for farming and wine production, but it’s also probably responsible for some really impressive chestnut trees. On the approaches to Europe’s most active volcano are living remnants from another time. Possibly the largest and oldest sweet chestnut trees in the world, surviving the threat of the woodman’s axe and diseases that have decimated other populations.

For centuries, these enormous chestnut trees were valued for their majesty as well as their bounty of nuts. They became local phenomena as well as tourist attractions for Europeans on the Grand Tour. Today, the two most famous: The Chestnut of 100 Horses and Chestnut of the Ship, are by far the largest of at least seven very old chestnut trees along the Etna’s Eastern slope.

About The Species

Credit:Benjamin Gimmel, BenHur, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) is native to Southern Europe and Asia Minor. Much like wine grapes it was introduced beyond its native range first by the ancient Greeks and later the Romans. This also gives a fairly firm upper age limit for Sicily’s chestnut trees. Some online sources claim ages as high as 4,000 years, however historical research and pollen analysis show the largest trees are about 2,000-2,500 years old.

It can take decades for a sweet chestnut tree to bear reliable harvests, but the largest trees can produce a bounty of chestnuts. Throughout Italy, regional specialties like pasta made from chestnut flour are found wherever chestnut trees flourish.

Sweet chestnut wood is hard, strong and rot resistant, making it highly prized for furniture, barrel making and timber framing. It is also a traditional source of charcoal and firewood. The practice of coppicing chestnut and other valuable trees was very common in Europe. This is the practice of ensuring repeated harvests of wood by cutting off the larger trunks and allowing new shoots to grow. Which makes these enormous specimens all the more significant.

Castagno dei Cento Cavalli: The Chestnut of 100 Horses

Credit: Rabe!, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Castagno dei Cento Cavalli or in Sicilian the Castagnu dî Centu Cavaddi, is within the Commune di Sant’Alfio, protected by an enclosure in a small park. Tree experts consider it the oldest known chestnut tree at approximately 2,500 years old, but some sources claim it could be almost twice as old. The tree is famous for its enormous size and has been hailed as the largest tree in the world by circumference.

The famous tree is magnificent when in full bloom, attracting travelers and inspiring artists and writers for centuries. Once the tree loses its foliage, it is less impressive looking, but you can see the three primary trunks that make up the 100 Horse Chestnut. The three main trunks of the 100 Horse Chestnut are large in their own right, but are also made up of multiple smaller trunks and new shoots from the base.

For the sake of clarity, the trunks of the 100 Horse Chestnut have their own individual names: Pollone Nord is the largest at 22 meters circumference, Pollone Sud at 21 meters, and the Pollone Piccolo at 9.3 meters. It’s believed that the main trunks all share the same root system and were once connected as a single tree, creating a circumference over 50 meters. Before the giant chestnut tree split into multiple trunks, it had a large hollowed out portion in the middle. Historic measurements have the tree’s girth at 57.9 meters, that’s nearly 190 feet of living tree, if accurate.

How Chestnut of the 100 Horses Got its Name

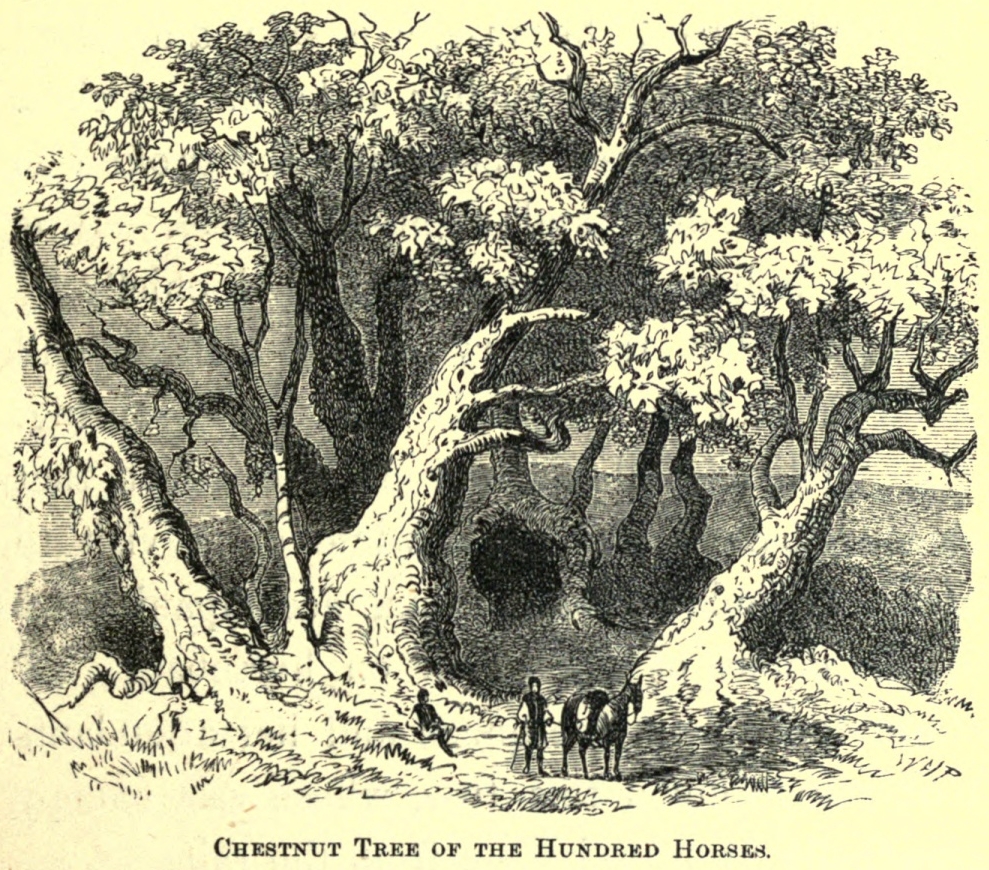

Credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In English, the tree’s name is often translated as the 100 Horse Chestnut or Chestnut of the 100 Horses. However, it could also been interpreted as the Chestnut of 100 Knights. Either way, the tree’s name is based on Sicilian folklore.

The best known story takes place in the late 15th century. Joanna of Aragon, Queen of Naples stopped in Sicily and visited Mount Etna on her way to Naples. Her entourage was accompanied by nobles from nearby Catania. The group was caught in a thunderstorm and sought refuge under this unusually large chestnut tree (castagno). Supposedly the huge canopy of leaves and the large hollow fit the entire entourage of 100 knights on horseback (Cento Cavalli).

The State of the Tree

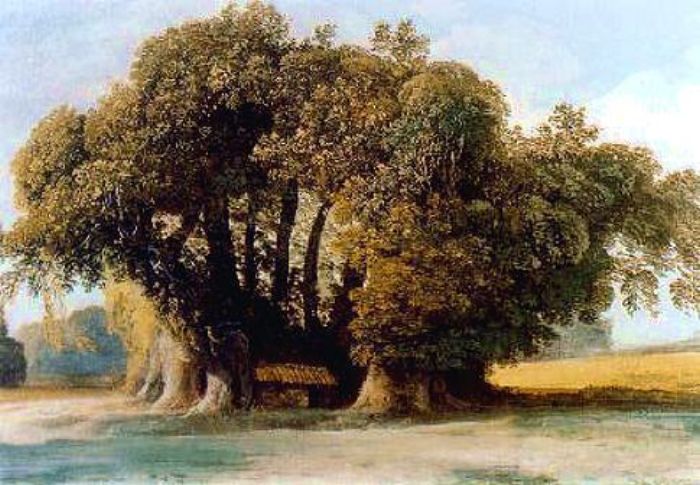

The French artist Jean-Pierre Houel spent time in Sicily during the 1770’s and gives a detailed description, along with a beautiful image of the tree. His work can be seen at the top of this article and shows a little house within the trunks, once used to store and roast the chestnut harvests .

Night not having yet come, we went at once to see the famous chestnut which was the object of our journey. Its size is so much beyond all others that we find it impossible to express the sensation we experienced on first seeing it. Having examined it carefully, I proceeded to sketch it from nature. I continued my sketch the next day, finishing it on the spot, according to my custom, and I can now say that it is a faithful portrait, having demonstrated to my own satisfaction that the tree was one hundred and sixty feet in circumference, and having heard its history related by the savants of the hamlet. This trees is called the ‘ Chestnut of a Hundred Horses’ in consequence of the vast extent of ground it covers.

– Houel, translation from: The Plant World (1897)

From: Useful plants: plants adapted for the food of man described and illustrated.

Public Domain

Not every visitor was so taken by the 100 Horse Chestnut as Houel. By the late 18th century, travelers remarked on how dilapidated the tree looked, and difficult to tell if the trunks were ever connected. Take a look at this one-star review by a snarky 18th century tourist:

I arrived at the celebrated chestnut tree, commonly called Il Castagno de’ Cento Cavalli, at three o’clock, after having been led astray several times by an inexperienced guide. This singular production of the vegetable kingdom, is composed of five old trunks, whose circumference may be about fifty paces, or one hundred feet, but they are so very much decayed, that it is impossible to recognize their having been united.

The ramification is neither picturesque nor extensive, and the house which was erected, for the reception of the fruit in the center of the trunk, is now fallen to ruins, and only presents a heap of stones to the view. Had I not been previously apprized of the state of this immense tree, I should have been much disappointed at that in which I found it; and was it not for the enchanting country you ride through to see it, I should not think it an object worthy the traveler’s notice.

There are several other large trees of the same nature very near it, one of which, called Il Castagno della Nave, (Chestnut of the Ship) is near twenty yards in circumference, and a healthy tree. Another nearly the same size, is termed Il Castagno della Navotta (Chestnut of the little Ship.)

– Letters From Sicily (1798)

19th century sources mention that the tree was struck by lightening at least once, causing burn damage that can still be seen. Jean-Pierre Houel states how the chestnut tree’s fame did not protect it from the harvesting of wood by the locals to roast the chestnuts. At some point, efforts were made to keep the trunks from splitting further by adding braces to support them as the heartwood rots out.

Nevertheless, the Castagno dei Cento Cavalli had become a tourist attraction over the centuries. Writers, poets, spoiled European rich kids, and local artisans have made the pilgrimage to see this famous tree. Some were left inspired, some, as above, disappointed. Nearly all of these visitors would also encounter another giant chestnut tree. This one may be less famous, but is arguably more impressive.

Castagno della Nave: The Ship Chestnut Tree

Also known as Castagno Sant’Agata.

Credit: AusTitz, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

This magnificent specimen, known as Castagnu a Navi in Sicilian, is located down the road from the more famous 100 Horse Chestnut, at Contrada Taverna in Mascali (municipality of Catania). The massive trunk sits along the SP84 road and partially held back by a retaining wall. The trunk is a solid mass where it meets the ground, except for a hollow that makes it reminiscent of the bow of a large ship. Above this “bow” of the ship, the tree splits into three main trunks. but is hard to determine how large it truly is.

Centuries of volcanic ash from Mt. Etna have piled up around the trunk behind the walls that separate it from the narrow road, making a full measurement impractical. Castagno della Nave is obviously a single trunk with a hollow, unlike the multiple trunks of Castagno dei Cento Cavalli. At over 23.5 meters in circumference, it is the largest chestnut tree with a single trunk.

Credit: Pietro Minissale

Although it is less famous than the 100 Horse Chestnut, the Castagno della Nave is important to the locals and has two more alternate names. The most common name today for the tree is Castagno Sant’Agata since it became a site of prayers to the locally popular saint.

Another alternate name for the tree is Arrisbigghiasonnu or the “wakes you up” tree in Sicillian. Supposedly the low hanging branches would hit snoozing wagon drivers along the road. However it may also stem from the abundance of chirping birds that can be found on the numerous branches, just across the road at bedroom window height.

Missing Giant Chestnut Trees

Some 18th and 19th century sources mention other chestnut trees in the area large enough to have been named, but it gets confusing. The dimensions and names of these trees don’t seem to line up with the documented surviving chestnut trees in the Etna region. The Ecomuseo del Castagno dell’Etna/Trucioli Association lists 26 monumental trees of various species in the area. Several large chestnut trees are listed, but are smaller than these historic references.

The celebrated chestnuts of Etna, however, merit particular notice. Many chestnuts thrive on the flanks of Etna. One is thirty eight feet in circumference: the Castagno de Santa Agatha’ is seventy feet in circumference; and the Castagno della Nave,’ sixty-four feet in circuit. A group of seven are called the seven brethren…

-The Physiology of Plants (1833)

A late 18th century Italian work on chestnut trees by Alberto Fortis, mentions two more “ship” related chestnuts in the Etna region: Castagno della Galea (the galley), and the Castagno della Navotta (the little ship). There is also some ambiguity about which tree is the original Castagno Sant’Agata since sources from this time all seem to consider it a different tree than the “Ship” chestnut.

There are several large and beautiful chestnut trees, many with multiple trunks in the general area, which makes it hard to say if these are cases of mistaken identity. They may also indicate the names of individual trunks of a larger tree systems like the 100 Horse Chestnut. Sadly, it is likely that these are once-documented trees that did not survive the axe, the blight, the bugs, lava flows, or the ravages of time.

Conservation Efforts

On August 21, 1745 the Royal Court of the Kingdom of Sicily issued a decree for the protection of both the 100 Horse Chestnut and the Chestnut of the Ship. A an early and historically significant example of conservation efforts, which almost certainly spared these trees as the once-dense forest gave way to cultivation.

These famous and ancient Sicilian chestnut trees have attracted a new group of admirers besides the tourists and artists. In modern times, the trees have been under scientific investigation by both professionals and amateurs. They are frequently measured and their annual growth rates are monitored. DNA testing has also been done and further testing is planned.

Today the Castagno dei Cento Cavalli is aging as gracefully as possible in its small park. Several organizations have measured and monitored the tree over the last decades. Both of these trees have become a sort of “bucket list” attraction for botanists, arborists and ecotourists.

The Italian tree conservation team of SuPerAlberi have measured the various trunks, taken DNA samples and monitoring the damage caused by insects. An invasive gall wasp from Asia has damaged the tree, its galls being a vector for dreaded chestnut blight.

The Castagno della Nave is located on private property but is easily visible for the public. This huge chestnut tree is also monitored by experts and is scheduled to undergo a pruning and enhancement project in 2025.

Which Chestnut Tree is Bigger?

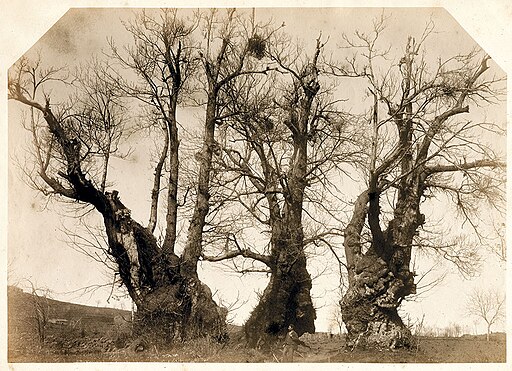

Notice man in the foreground.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Guinness Book of World Records listed the 100 Horse Chestnut as the world’s largest tree using a measurement from 1780. However, modern researchers are not so quick to award the Castagno dei Cento Cavalli the crown as the largest tree. The question hinges on whether the tree was a single trunk that split over time, or if it was always 3-4 smaller trees that have fused their roots together. Two of the largest trunks are further divided into several smaller trunks, making accurate measurements more difficult.

The image above from 1895 may be the best photographic evidence that the trunks were once connected at their base. Only further DNA testing will prove they all come from the same root system. If true, then the Castagno dei Cento Cavalli will be undisputedly the world’s largest tree by circumference. Because of this ambiguity, the individual trunks are often measured separately.

None of Cento Cavalli trunks, are as large as the massive trunk of the Castagno della Nave. There is no denying how massive the trunk is, with an estimated 88 cubic meters of total volume. This possibly makes it the most massive native tree extant in Europe.

Special thanks to Lavinia Lo Faro of the Ecomuseo del Castagno dell’Etna and botanist Pietro Minissale of the University of Catania for providing excellent information about these famous trees and the surrounding ecosystem.

Sources/More Information

Camus, A. (Aimée). Les Chataigniers: Monographie Des Genres Castanea Et Castanopsis. Paris: P. Lechevalier, 1928.

Fortis, Alberto. Della Coltura Del Castagno Ne’ Monti Di Boscati Della Dalmazia Marittima, E Mediterranea: Discorso Recitato Nella Prima Session Della Società Economica Di Spalato Del 1780. Venezia, 1794.

Giant Trees Foundation: Castagno dei Cento Cavalli

Italian Botanical Heritage: Castagno della Nave

Monumental Trees Entry: Castagno dei Cento Cavalli

Monumental Trees Entry: Castagno della Nave

Murray, John. The Physiology of Plants, Or, The Phenomena And Laws of Vegetation. London: John Murray, 1833.

Richards, Thomas Bingham. Letters From Sicily: Written In the Year 1798. London: Printed for the author, by W. Stratford, and R. Young, 1800.

Tornabene, Francesco. Saggio Di Geografia Botanica Per La Sicilia. Napoli: Fibreno, 1864.

Useful Plants: Plants Adapted for the Food of Man Described And Illustrated. London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1870.

Vincent, Frank. The Plant World: Its Romance And Realities: A Reading-book of Botany. New York: D. Appleton and company, 1897.