Ports and waterfronts always attract a rough crowd and that crowd is usually up for some equally rough entertainment. After the Civil War, Gloucester, Massachusetts was one of the most renowned and saltiest of fishing ports in the world. A harbor with hundreds of fishing schooners and even more transient fishermen living in boarding houses. Ships from Europe, unloading salt for Gloucester’s salt cod, had rowdy crews looking for a good time. As the quasi-legal sport of boxing, more specifically prize fighting, grew in popularity, it fit right in along with the bars, brothels and banks of downtown.

There was a brief time back then, when the Gloucester Athletic Club doubled as a venue for seeing prize fights. Hosting some of the big names of the days when boxing gloves were a new thing and the finer rules were still being ironed out. Legends like Sam Langford and Jack Johnson fought here, along with many other names that were once well-known in boxing’s early days.

Not only did Gloucester hold bouts, but there were also a few early prizefighters that hailed from America’s Oldest Seaport. While none were really famous boxers, two of them were certainly infamous in their day, both in and out of the ring. Here is glimpse of Gloucester boxers from the early days along with a few wild stories that can only come from the world of pugilism.

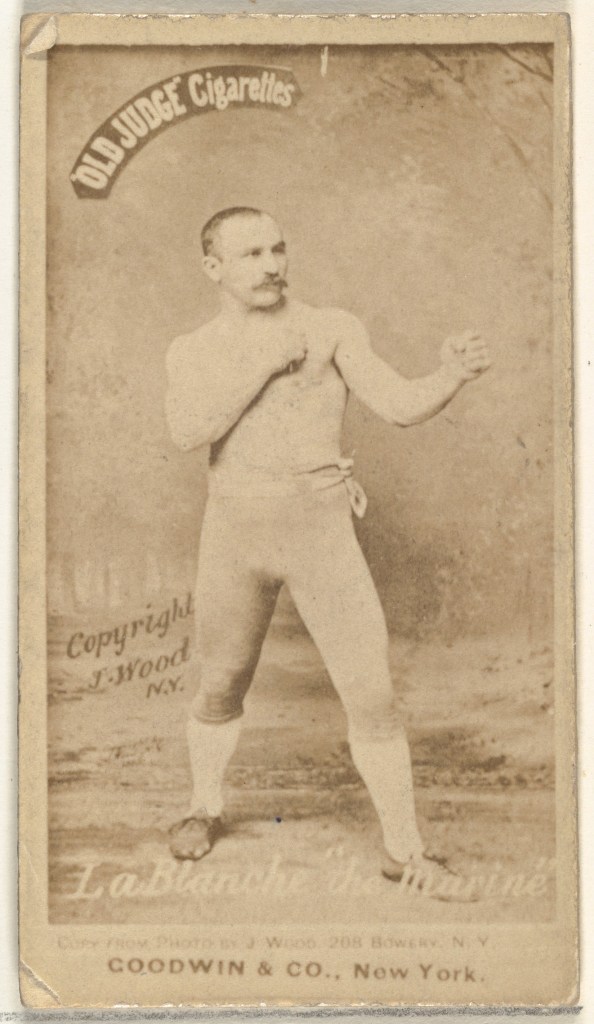

George LaBlanche: “The Marine”

Celebrities and Prizefighters series for Old Judge Cigarettes.

Credit: Public Domain from MET Museum

George LaBlanche (spelled variously) was born in 1856 as Georges Blais in Quebec. He was a former lumberjack, and served in both the Canadian Army and US Marine Corps. He stood about 5 feet, 7 inches and weighed in at 150-165 pounds, technically making him a middleweight in the vague divisions of the time. He fought men much larger and also would cross the “color barrier” to fight black boxers, which many big names like his good friend John L. Sullivan, would not.

LaBlanche began boxing in the Canadian military, before getting his discharge and joining the US Marines. All signs point to a heavy drinking problem, a sign of things to come, and was declared unfit to serve after only six months. This disgrace did not stop him from fighting as “the Marine” George LaBlanche.

At the start of his professional boxing career in 1884, he lived in Gloucester, Massachusetts and the town directory lists him working as a clerk. He fought in town as well, in August 1885 he beat Vermont’s heavyweight champion, C.E. Randall at the Western Avenue Athletic Club.

Jack Dempsey and the Infamous Pivot Punch

While “the Marine” may have faded from boxing memory, an infamous banned punch is named after him. This is the “pivot punch” also known as the “LaBlanche swing” and it took place against a famous boxer.

Before there was THE Jack Dempsey, there was another boxer of the same name and just as famous: “Nonpareil” Jack Dempsey. The better-known Dempsey fought under the name “Jack” in honor of the original Dempsey. The “Nonpareil” was already the American middleweight champion at the time and many considered him the best fighter of his day. The two men had already fought, with Dempsey winning and the rematch was set for August 27, 1889 in San Francisco, California.

Much like the first bout, Dempsey was proving the superior boxer when LaBlanche did something unexpected in the 32nd round. The story is his trainer taught him something called a pivot punch: LaBlanche threw a short left that missed Dempsey, but it was a feint. LaBlanche spun on one heel and spinning around like a discus thrower in reverse, hitting Dempsey in the jaw with the back of his right hand. Down went Dempsey and shortly a new rule banned this so-called “LaBlanche swing”. The referee awarded the fight to “the Marine” but the Athletic Club did not award him the middleweight title from Jack Dempsey. That didn’t stop LaBlanche from calling himself the new champion however.

From here, LaBlanche’s career heads south. In one fight he was disqualified for kicking his opponent, George Kessler. In 1891 he threw a fight against the undefeated Young Mitchell, later admitting he told his friends to bet on Mitchell to win in the 12th. Once it was discovered LaBlanche threw the fight, Mitchell was absolved, and the purse withheld.

The Marine’s Downward Spiral

Like many older and injured boxers, with no exit strategy, the Marine kept fighting even as the losses piled up. Outside the ring he lived beyond his means, was an abusive drunk and a thief. LaBlanche’s final boxing years were often interrupted by stints in jail. Newspapers would report on his crimes and how far the once famous pugilist had fallen. Towards the end, he would request jail time after an arrest in order to sober up. George la Blanche died in Lawrence, Massachusetts on May 3rd, 1918.

Sailor Brown: US Navy Champion

Public Domain

Charles “Sailor” Brown was born in 1863 in Gloucester to a fishing family and spent a few years fishing and fighting in his hometown. Charles enlisted in the US Navy in 1882 and quickly began his boxing career. While stationed aboard the receiving ship USS Dale, he defeated the best boxer on board. Sailor Brown was a middleweight like George LaBlanche, standing about 5 feet 6 inches and weighing 152 pounds. His Naval boxing career saw Brown give up quite a bit of height and weight to his opponents, but apparently went undefeated.

When stationed aboard the USS Tennessee, he defeated the English Navy champion John McMillan in a 30 minute brawl that primed him for a professional career. He was discharged in 1885 and defeated the Navy’s middleweight champion. In a Philadelphia Boxing venue known as Arthur Chamber’s “Champions’ Rest” Sailor Brown knocked out a man a night for a week.

His initial success was eventually overshadowed by his defeats. On the West Coast in 1889, Sailor Brown was reported to be a “poor representative of a pugilist” by the National Police Gazette even before his embarrassing loss to local champion Young Mitchell. The same boxer who faced “the Marine” a few years later. The Sailor Brown-Young Mitchell fight was expected to be a good one, but the spectators were left underwhelmed.

The National Police Gazette – March 1889

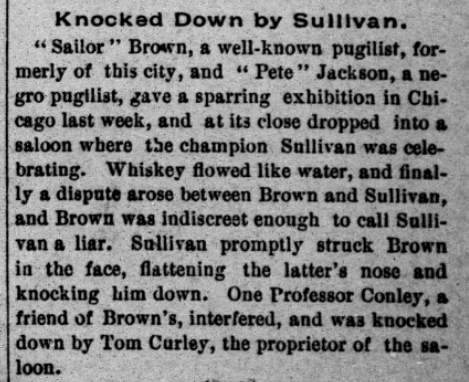

Meeting the Fist of John L. Sullivan

Boxing fans would often claim to have shaken the hand of famous heavyweight John L. Sullivan, turning it into a popular expression: “You shook the hand that shook the hand of John L. Sullivan.” Well, one night in Chicago after a bout, Sailor Brown got acquainted with Sullivan’s fist.

Digitized by Sawyer Free Library

Sailor Brown vs. Sailor Tom Sharkey

Sailor Brown had two encounters with another champion Navy boxer: “Sailor” Tom Sharkey, whose legacy carries on today as one of Boxing’s greatest punchers. On their first meet up in 1895, Sharkey knocked down Sailor Brown seven times in the first round. To survive, Brown clenched Sharkey before he could knock him out, and an angered Sharkey was disqualified for tossing him. Their second bout did not fare any better for Sailor Brown in the ring, and worse on the scorecard, getting knocked out in the second round.

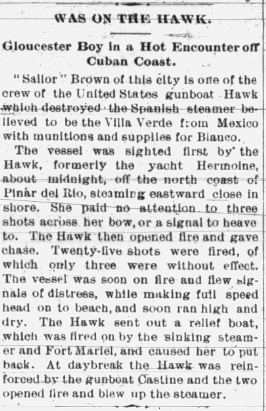

Sailor Brown Goes to War

When war broke out with Spain in 1898, Sailor Brown returned to the Navy, where the Gloucester Daily Times reported on the exploits of their native son.

Digitized by Sawyer Free Library

In the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, Gloucester made sure it was known that their native son was the only boxer of note to enlist. They also made sure to embellish his record as well, claiming he defeated Sharkey on at least one occasion.

Sandy Ferguson: Boxing’s Stubborn Child

Public Domain

“This is the story of the bad boy who didn’t reform. It is not fiction. It is a true story, and for that reason the publisher would doubtless turn up his nose at It. And yet, it is nonetheless a good Story. John H. Ferguson, the “Chelsea Strong Boy,” would be a fascinating subject for some latter day Dickens.”

The True Story of a Stubborn Child – Boston Sunday Post April 7, 1907

One of the more colorful prize fighters of Gloucester’s past was John “Sandy” Ferguson. Known as “Big Sandy” the “Chelsea Strongboy” and most famously “The Stubborn Child” as dubbed in the press. In an age of bad-boy prize fighters, Sandy was notorious for his exploits outside the ring. His short, fast and problematic life is nearly a blueprint for hard living “palookas” in both fiction and real life. If the term existed during his career, “Big Sandy” would certainly have been called a palooka, toward the end.

Sandy was born in Moncton, New Brunswick, on July 24, 1879 but his family moved to Chelsea, Massachusetts when he was 13. In 1898, Sandy began a career in boxing and standing 6 foot 3, he was aptly named “Big Sandy” in the press. He was not technically sound, or even in shape most of the time, but he was a big heavyweight, could take a beating while sometimes giving one.

He would basically fight anyone, talked trash the whole time and had no problem fighting dirty. He once claimed he could wrestle, but that experiment lasted 12 seconds when he lost to a Turkish wrestler on April 4, 1901. His boxing career on the other hand, started better. His career got a boost later that same month from his lighting quick knockout of Gloucester’s John McDonald in 21 seconds at the Athletic Club. He would then travel to England and return claiming to hold their heavyweight title.

“Sandy” Ferguson, who hails from Boston, recently defeated a man named Ben Taylor in London and on the strength of that victory pretends to lay claim to the distinction of being the heavyweight champion.

The National Police Gazette: March 29, 1902

Sandy would fight most of the big names of the era regardless of size or color: “Denver” Ed Martin, Joe Jeannette, Joe Walcott, Kid McCoy, Klondike, and Sam Langford. Most significantly however, is his history with Jack Johnson. Between 1903 and 1905, Sandy fought the “colored champion” five times, at at time when many white heavyweights were dodging Johnson. Once Johnson beat Tommy Burns in 1908 for the world heavyweight championship, the “stubborn child” was briefly considered a “White Hope” by fans and promoters who couldn’t accept a black world champion.

Sandy Ferguson in Gloucester

Sometime after returning from England, Sandy married a Gloucester girl, whose family ran a boarding house for fishermen in the hard working, but also hard drinking Duncan’s Point neighborhood. Some of the rowdiest saloons on the East Coast lined what was affectionately known as “Drunken Street” right down to the wharves. Full of rough sailors and fishermen back from the Grand Banks, Sandy must have been right in his element.

Even when things were going well, Sandy was his worst enemy and was just an all-round jerk. He was a big goofy kid when sober, which was not often, and a total menace to his family and the surrounding neighborhood otherwise.

“Sandy was known as a stubborn child, and although he has grown sufficiently to be in the heavyweight class, he still retains many disturbing proclivities. he is always aching for a fight, but his most frequent bouts are with John Barleycorn, and invariably John has knocked him out.”

The National Police Gazette: April 4, 1906

The local press along with correspondents for The National Police Gazette followed his exploits like tabloids and TMZ today. He was always getting in trouble for stealing, hitting his wife, or friends and various other crimes. In one example from 1907, Sandy left town for Philadelphia, ostensibly to challenge Jack Johnson again, but just so happened to leave town the same time as his wife was filling out a warrant with the police for lack of child support.

Sandy Messes with the Wrong Fisherman

In other towns, a big jerk like Sandy could probably have gotten away with much more, not in early 1900s Gloucester. The saloons he frequented were filled with fishermen who stared death in the face as if was just a day at the office. These men loved prize fighting and all manner of rowdy fun, but none of them would tolerate Sandy’s antics for long. The best known example happened in the restaurant of Pete Steele, a 60 year old retired dory fishermen.

Sandy was being his usual obnoxious self to the waitress, demanding an apology for some imagined insult, when he started hurling a dinner plates at the girl. Pete heard the plates smashing against the wall and made his way to the front. The big old fisherman leaped over the counter and clocked Sandy with a straight right, knocking him to the dining room floor. Steele proceeded to grab the heavyweight and toss him out the door like a box of fish.

Picking himself up, Sandy proceeded to attack the storefront, punching out the plate glass window and cutting himself up badly. He was arrested for “malicious mischief” and claimed once he sobered up he would be back for a rematch with Pete Steele.

When told that Ferguson proposed to come back and have it out, Mr. Steele did not appear in the least alarmed. He said ‘I’m not looking for trouble, but if he comes back here he will get all he wants.’

Gloucester Daily Times: September 17, 1904

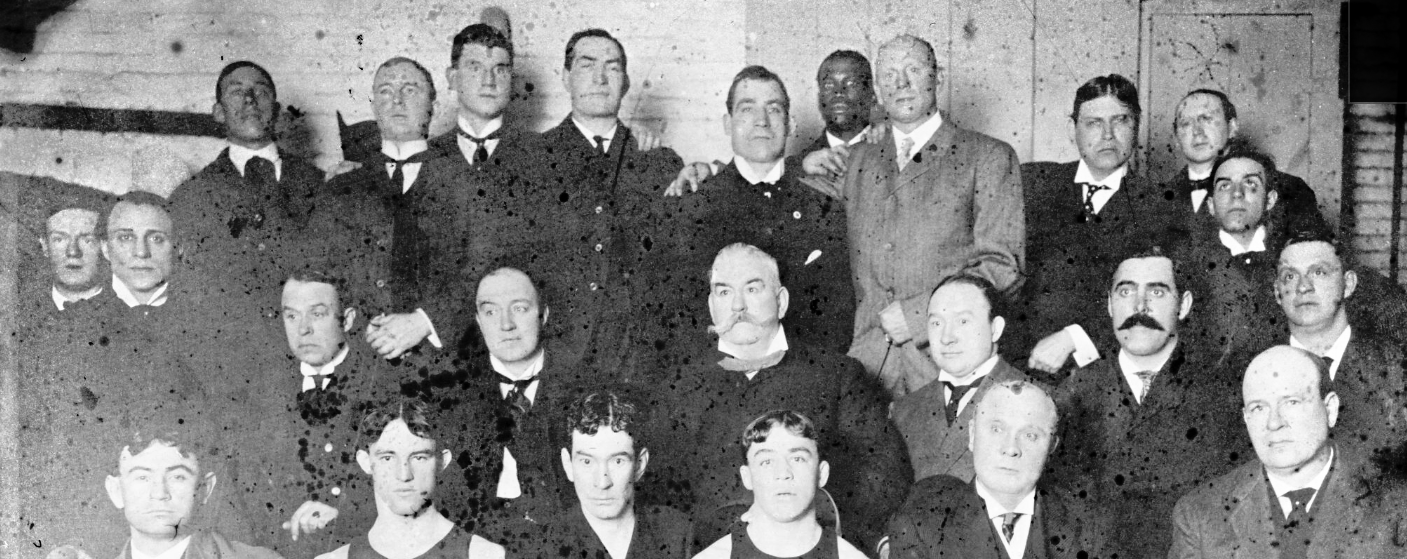

Jack Johnson in Gloucester

Jack Johnson and Sandy Ferguson are in the back row center.

Credit: Boston Public Library

Salty old Gloucester was somehow able to draw the most famous boxer and most controversial man in America of the time. On June 8, 1906 the Gloucester Daily Times briefly mentioned that Jack Johnson was in town as a guest of Jack Diamond, who was Sandy Ferguson’s trainer. The Athletic Club was eagerly attempting to set up a match with a local fighter, which ended up being Lowell’s Charles Haghey.

Digitized by Sawyer Free Library

Ten days later on June 18, 1906 Jack Johnson knocked out Charley Haghey in the first round. The crowd was expecting a much longer fight, which was scheduled for twelve rounds. Johnson entertained them by putting on five rounds of exhibition boxing against Jimmy Murray, his sparring partner and protege.

Jack Johnson either stuck around Gloucester, or returned a week later to help his protege Murray, take on Gloucester’s Joe Lavoie on Monday June 25. The match ended with a decision to Lavoie, but was considered a good exhibition by the Gloucester Daily Times. However, beyond the blow by blow, the paper sheds light into some of the pre-fight entertainment of the day:

The bouts were not started until 9 o’clock. Prior to that a mandolin and harmonica artist entertained the audience and then passed around the hat, reaping a rich harvest of nickels and dimes. A little Italian girl and boy who have been playing and singing on the streets then entered the roped arena and performed, the girl passing around the hat and making a rich haul.

Later Jack Johnson, the colored heavyweight champion, entered the ring with the pair, towering like a Colossus of Rhodes above them, and banged the tambourine, after which he passed around the hat, securing another rich harvest for the boy and girl.

Gloucester Daily Times June 26, 1906

Jack Johnson and Sandy Ferguson Go on a Bender

Public Domain

The relationship between Jack Johnson and Sandy Ferguson must have been complicated. If you look at their fight record, Sandy’s dirtiness in the ring, and Johnson’s own words in his autobiography, it’s hard to imagine these two being chummy. Yet there they were, sometime after Johnson became the world heavyweight champ, on Gloucester’s “Drunken Street” tearing it up.

This story was recounted in the Gloucester Daily Times by Vincent Daniels, a retired Boston police officer who started out in these crazy days as a “Duncan Streeter.” He recalled the day as a kid, when Jack Johnson returned to Gloucester with Sandy Ferguson, but not to box. Daniels assumed the Champ joined Sandy to have some rowdy fun in Gloucester, away from the press in the big cities.

By this time (post 1910) Sandy was estranged from his Gloucester wife, but still came to town to get drunk and cause mischief. This time was no different, except he had one of the most famous men in the world with him. The two heavyweights went from bar to bar up and down the street, the kids of Duncan’s Point following them. At one bar, Sandy began his usual nonsense and demanded a fisherman buy a round for everyone in the crowded saloon. As the argument heated up, the kids watched through the window as Mac the barkeep leaped over the bar, grabbed Sandy by the collar and tossed him into the street. What happened next is the stuff of legend:

Then Mac took Jack Johnson by the coat collar and the seat of his pants, and tossed him out too. Johnson landed on top of Sandy on the sidewalk. In a moment they got to their feet and went arm in arm along to the next nearest bar, on the corner of Rogers Street.

-Vincent Daniels

Apparently Mac knew Sandy all too well and would have none of it. However he had no idea who the large, and probably very well-dressed, black man was that he so casually tossed out the door. Daniels said that when the fishermen told Mac he just tossed out Jack Johnson, the heavyweight champion of the world, he keeled over and fainted.

Gloucester never lost its love of boxing, but the days of hosting prize fights were short lived. By the time Jack and Sandy got bounced by Mac, professional fights were no longer hosted in town. There were still plenty of rowdy pursuits along the waterfront, still plenty of fights and many more stories to share.

Sources/More Information

Cape Ann Advertiser, Gloucester Daily Times. Digitized by Sawyer Free Library/Advantage-Preservation

Daniels, Vincent. He Bounced The Champ. Gloucester Daily Times, Gloucester, MA, 2-3-1961

Edwards, William, Portrait gallery of pugilists of America and their contemporaries. Pugilistic Publishing Co. Philadelphia, 1894.

Eisen, Lou. George La Blanche Canada’s Original World Champion

Fox, Richard Kyle, The Life And Battles of Jack Johnson: Champion Pugilist of the World. New York, 1912.

George LaBlanche boxing record from Cyber Boxing Zone

Kent, Graeme. The Great White Hopes: The Quest to Defeat Jack Johnson. United Kingdom, History Press, 2005.

The National Police Gazette. Microfilms available on Internet Archive

Nicholson, Kelly Richar, Hitters, Dancers and Ring Magicians: Seven Boxers of the Golden Age and Their Challengers. McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2010.