I’ve never been a soldier, but I have a huge respect for anyone that has served in any capacity, either in war or peace. I’m proud of my family and friends who have served and have tried to absorb as much information about their experiences that they want to share. When you study history and anthropology, the topic of war is always present. Wars leave scars – in the history books, the archaeological record, and within the people and cultures affected.

War is ingrained in our primate DNA and for large portions of human history, it was glorified. Going off to war was a right of passage, an act of manhood in the age of swords and simple firearms. All that changed during the First World War. A war described by one of my professors as “A 19th century war fought with 20th century technology.”

My late friend Jim went through hell during World War II, but he could only imagine the horrors his father faced in 1918 at the “meat-grinder” of Belleau Wood. He was not the only member of the Greatest Generation that has spoken to me in awe of those poor bastards that fought in the trenches. It was the first modern war, with the first modern war casualties – both physical and mental. However it was strategized by generals who still dreamed of cavalry charges and fought by men, some of them boys, who had no idea what lay ahead. This is when the term “shell shocked” enters the zeitgeist.

World War I is almost a forgotten war in the US, partly due to the fact we only participated towards the end. We didn’t learn much more than the “Flanders Fields” poem, Woodrow Wilson, and the League of Nations in high school. Of course, movies helped shape my view of what the Great War looked like. I took an excellent class in college on modern warfare that explored World War I in depth, including the somewhat neglected Eastern Front. Today, the internet and especially YouTube has given The Great War a closer look, opening up a wealth of information on the supposed “war to end all wars.”

Backpacking in Bruges

Credit: Historical Vagabond

My first real education in World War I happened on a wet and foggy Belgian day in the spring of 1996. I was 19 and nearing the end of a three-month backpacking trip with a friend and a girl from Oregon who joined us along the way. By early April we had made it to the charming medieval wool town of Bruges, back when there were actually off-seasons. We backpackers had the town to ourselves and the locals were great. The three of us strolled around the canals, with no plan in mind, eating Belgian french fries – frietjes with a variety of different sauces. I’m pretty sure it was the first time I tries fries with samurai sauce.

We stayed at de Passage, which at the time was a Grand Cafe with a hostel upstairs. Today the accommodations look a little more upscale, but the Cafe still looks the same. Passage also gave me an education in Belgian beers with their impressive selection. Their beer menu is written on mirrors surrounding the cafe, which covered everything from the famous brands like Duvel to the then-obscure Trappist types like Orval (my favorite) and all the way to the various fruit flavored beers.

Today the beer universe has exploded, but back then most of these beers were hard to find in the US. And I was also 19, back home we drank cheap beer after finding someone to buy it for us. Over our stay in Bruges, the three of us attempted to try every single beer they had. Some of the weird ones, like banana flavored beer, we had to share a small bottle. I have no idea how anyone could drink a whole bottle of that, it was really gross.

While we were drinking our way through the beer menu some travelers we met earlier were coming back from a Belgian chocolate and beer tour by a local company. That sounded like fun so we decided to sign up for one in the morning. A few minutes later the bartender came up to us and said tomorrow’s tour was of the World War I trenches and cemeteries. Well, it seemed less fun, but fortunately I was traveling with people that were always up for something new. Looking back, I’m pretty sure we got a much more memorable experience.

Flanders Fields Battlefield Day Tour

I apologize in advance for my switching between the French and Flemish Dutch place names with no rhyme or reason.

The tour company was called Quasimodo Tours, and am glad to find that they are still going strong today. It is a husband and wife team of Sharon and Philippe, he’s a local and she’s from Australia. After three months of travel, we had hung out with dozens of Aussies and Kiwis, so we caught right away that our Belgian tour guide Philippe, had picked up a bit of Australian style English. We all hopped in the van as the rain started and headed out of town towards the Western Front.

The three of us were seated in the back of the van, looking out to a patchwork of tilled fields and clean, organized Flemish villages. Philippe got on the mic and started describing the area, and making the best of the weather situation. It may not have been a nice day, but he said it is a much more accurate and appropriate way of experiencing the battles of Ypres.

The Ypres Salient

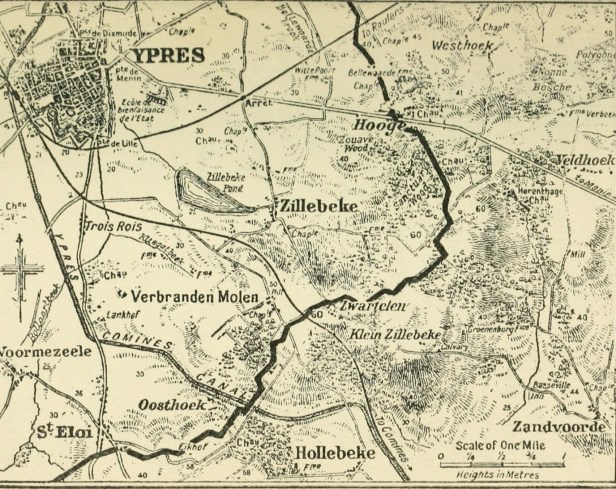

Less than a century before our tour, this small corner of Belgium witnessed some of the most horrific destruction in human history. Over the course of the war, a salient, or “bulge” was created into the German lines by the Allies. This well fought-over Western Front is still often referred to as the Ypres Salient.

With the Germans pushed to relatively higher ground on Passchendaele ridge, they also had clear views of the trenches, supply lines and towns within the salient. Five separate operations known as the “Battle of Ypres” ensured that this small patch of Belgium was active nearly the entire war. The third such battle, known as Passchendaele, is alone responsible for at least 500,000 total casualties in about three months.

For a local like Philippe, this isn’t just world history, this is local history and you could tell that this is not just an idle hobby. He reminded us as we drove around, that every village and town was pummeled to rubble and all this farmland was churned into a cratered moonscape of wet muddy clay from four years of near constant bombardment.

Every battlefield in this area is a war grave, thousands of young men who died in No Man’s Land were never recovered. Every farm that grew back after the war, to this day gets a secondary crop of unexploded munitions, the so-called “Iron Harvest”. Our guide Philippe told us when they played army as kids, they played with real bayonets and grenades found in the mud. I believed him since if we would have done the exact same thing.

After all this time I don’t recall the actual order of events. I also have a feeling that the weather may have cut short some of the minor outside visits, but here are the major stops we made. Thanks to Google StreetView, I attempted to retrace the route from Bruges to help jog my memory. I did take photos, but this was the age of film, and I was a 19 year old nitwit with a point and shoot camera. I thought I took more pictures, but it must’ve been the camera in my mind. I am grateful to Sharon and Philippe for helping me fill in gaps in my information as well.

Georges Guynemer Memorial

Credit: Wernervc, CC BY-SA 4.0

“Until one has given all, one has given nothing”

We entered the small village of Poelkapelle but we didn’t stop, instead the Guide began telling the story of a famous French Ace. In September of 1917 France was in turmoil, news broke that Georges Guynemer, the French Ace of Aces with over 50 victories, went missing in action over the villages of Langemark-Poelkapelle. His body was never recovered, most likely destroyed by an artillery barrage following his dogfight.

The memorial to this famous flying Ace is located in the middle of a small traffic rotary (roundabout) in Poelkapelle. With the rain coming down, we slowly drove around the monument. A stone pillar is crowned with a bronze statue of a stork in flight. This was his squadron’s symbol, not unlike a coat of arms for these modern knights of the sky. Guynemer was a national hero, and is still remembered in France today. A fighter squadron is named in his honor and they continue to use the stork emblem.

The Brooding Soldier

Copyright Jan Dharted

The first actual stop I remember was to a very stoic memorial on the outskirts of the village of Sint-Juliaan. A granite obelisk is carved into an effigy of a Canadian soldier, head down, hands resting on his rifle in a mourning posture. The rain falling down on the soldiers helmet made the monument hovering over us, even more impressive.

The memorial honors the Canadian First Division, who faced the first poison gas attack of the war on April 22, 1915 during Second Battle of Ypres. Over a 48 hour period the division was decimated: one out of every three became casualties, one out of every nine were killed. As Philippe told the story of how the chlorine gas blew around with the wind, wreaking havoc on the lines, the experience began to sink in. I looked around at bucolic farmland and quaint brick buildings and imagined the hell on earth the area must have been like.

Tyne Cot Cemetery

In a gray mist we drove through an area that was the scene of fierce fighting and near constant bombardment for years. We learned how the whole area turned into a churned up quagmire of mud and clay, how wounded men drowned in the mud. Even the dead could not rest as their graves in No Man’s Land were blown to bits every time the front lines moved. By the time many of these men found a final resting place, they were impossible to identify. Even more were never found at all.

Our next stop was the Tyne Cot Cemetery, the largest cemetery for British Commonwealth forces in the world, for any war. In my opinion, it is also one of the most beautifully designed and sited war cemeteries. Over 8,000 buried soldiers are unnamed, we were amazed at how many of the white marble stones were engraved with the laconic phrase: A soldier of the Great War

What I find so moving about this place is its location: established on a portion of the German front lines. Concrete pillboxes are incorporated into the memorial. Looking out from the direction of those pillboxes, towards the former No Man’s Land, I imagined what it must have looked like during the Battle of Passchendaele. The damp air and gray sky muffled the surrounding noise, giving the cemetery an eerie quietness.

In my head, my overactive imagination replaced the quiet with the sound of artillery and machine gun fire. Of men and horses screaming and bi-planes jousting overhead. The beautiful green countryside all around me was replaced by craters, mud and jumbles of barbed wire. For a brief moment, I could feel it. A surreal experience that I will never forget.

Ypres-Ieper

We drove into the charming Flemish town of Ieper (Ypres in French) and stopped for a bit in the main square to check out the famous Cloth Hall. This is one of the largest non-religious structures from the Middle Ages and an imposing testament to Ypres’ cloth trade empire. In the gloom and drizzle, surrounded by those typical Flemish/Dutch style stone buildings with soft lighting in the windows, gave off that cozy feeling they call gezelligheid, while I was getting cold and soaked.

Credit: Quasimodo Tours

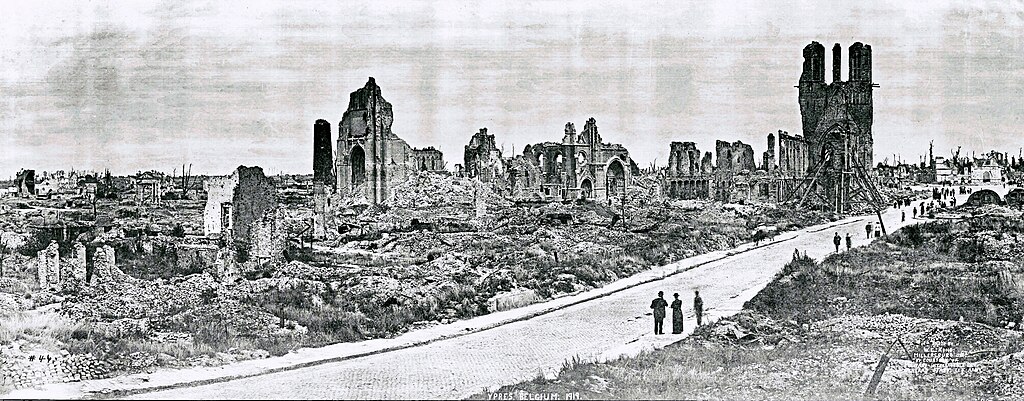

Back in the van our guide showed us a photo of what this very spot looked like during the Great War…

Cathedral tower on left, Cloth Hall tower on right

Ieper/Ypres, known to the British Tommies as Wipers, was located right in the path of Germany’s Schlieffen Plan. Their ideas of sweeping right through Belgium and on to Paris dissolved into the famous “race to the sea”. The Western Front became entrenched and the first of what would be five separate Battle of Ypres began in October of 1914.

The constant bombardment this small, but historically important town faced during the Great War was unprecedented. Ypres was an important location for the Allied supply lines and troops coming to the Front. The Germans used their superior position to rain down artillery fire for the entire war. There really wasn’t much left of Ypres, and there was serious consideration for leaving the town in ruins as a memorial.

War reparations paid by Germany allowed Ypres to start rebuilding in the early 1920’s. The famous Cloth Hall and Sint Maarten’s Cathedral were reconstructed, using surviving material where possible. Today, if you look closely at the Cloth Hall’s facade, you can see the bullet holes and other damage on the stones. Since our visit there is now a really nicely done war museum located in the Cloth Hall

Menin Gate

Down the road from the Cloth Hall is the famous Menin Gate, built into the old town ramparts. The original town gate faced the town of Menin-Menen, hence the name, and was repeatedly bombarded by German artillery during the war. In the 1920’s the gate was rebuilt as an impressive memorial.

The Menin Gate Memorial is for nearly 55,000 Commonwealth soldiers who fell in the Ypres Salient with no known grave. Even then, the memorial is not big enough to contain all the names of the missing. I thought about that staggering number, and the very small patch of Belgium this all took place. In this tiny corner of this tiny, flat country, each battle was like a war unto itself, with all the destruction and death hyper-concentrated into a postage stamp strip of countryside.

As we looked at the reams of names carved throughout the Gate, our guide reminded us that it was unlike some memorials to the fallen. The names here are not just the war dead, everyone of these names are men who are missing. When you let that sink in, it is chilling. I can only imagine what it is like to experience this through the eyes of a veteran.

Credit: Quasimodo Tours

The fact that the names etched on the memorial walls are still remembered is incredible. Many names had paper red poppies placed by the descendants of the fallen. To still have this connection between the British Commonwealth and the people of Flanders, after all this time, is just so incredibly rare and very moving.

The Last Post

I didn’t witness this event, but I feel it is important to mention the tradition of The Last Post.

Every evening at 8.00PM the police stop traffic at the Menin Gate to allow buglers to play “the last post”. This is the bugle call played at the end of the day, opposite to the better known reveille. The local, non-profit Last Post Association has been performing this ceremony since 1928 to honor these soldiers. The Last Post has been performed at the Menin Gate every night, with the exception of the German occupation of Belgium in World War II.

There has got to be a lesson here for the rest of us. Maybe if the rest of the world kept the candle of memory burning like they do here, how they remember the horrible losses, and how senseless and worthless it all was, maybe the Great War could have been the war to end all wars. Wishful thinking on my part, what they have in the Ypres Salient is rare and special

Hellfire Corner

Heading out of Ieper, about a mile from the Menin Gate we came to an unassuming traffic roundabout. Out guide explained how this road was vital for Allied troops and supplies. However it was in plain sight of the German Artillery and was one of the most dangerous places in the entire Western Front. Shells hit this spot on average every 5 seconds during the worst of it. The British Tommies, famous for their brand of gallows humor during the Great War, began calling it “Hellfire Corner”…because it was the hottest spot on earth.

There was still more to see on this incredible tour of the Ypres Salient, but I will break here and pick up the story in the next installment. Thank you all for reading.

Even here, the horrors of WW1 have been obliterated by WW2 in many ways. Apart from seeing the places, some wartime memories from well-known poets are a way to find out how Ypres worked in the minds of that generation, and of course, in every village of my country, you find memorial sites for those from the place who died on all fronts.

For a number of decades, we believed that the experience of WW2 had “ended all wars” in Europe. Unfortunately, that was an illusion, too.

Thanks for sharing!

We spend a fair amount of energy looking into the history of a place when we visit. It rounds out the experience. Nice piece!

Thank you!